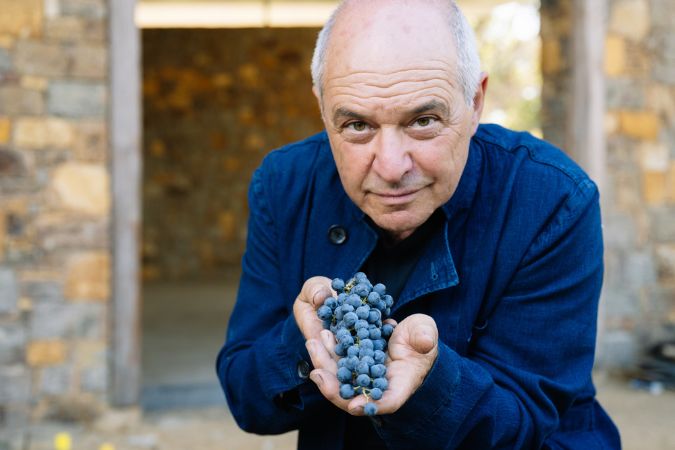

Will Berliner says he didn’t drink wine until he was in his 50s. There might have been the odd bottle of Thunderbird in his teens – he’s a New Yorker by birth – but that was all. ‘All I knew was that white wine was for girls and red wine was for guys. I never drank it.’

So it’s remarkable that now, in his 70s (he looks a decade younger), he’s producing a wine that has been lauded since its first vintage in 2010. Cloudburst, from Margaret River in Western Australia, has been described as ‘otherworldly and memorable’ by Matthew Jukes; ‘fearless and uncompromising’ (Huon Hooke); and ‘a gorgeous wine’ (Jane Anson). It joined the mighty John Riddoch and The Armagh as the first Australian wines on the Bordeaux Place. ‘Will works in ways that are completely different to the mainstream. He’s doing amazing things and his wines are excellent,’ Andrew Caillard MW, author of The Australian Ark, told me.

In minimalist, etched glass (screwcaps on both red and white), Cloudburst wines sell for between £130 and £200 per bottle. It’s one of the most expensive Margaret River wines but given that it’s vanishingly rare – Berliner makes about 250 cases of Chardonnay, 200 of Cabernet Sauvignon and 50 of Malbec (it can be much lower – there was less than half that in 2022) – that’s pretty good value.

We meet downstairs at Hedonism in London’s Berkeley Square. ‘There he is!’ Berliner says, as if it’s me who’s the celebrity. He’s compact, fit-looking and energetic; from the moment we sit down, he barely draws breath in his urge tell the story of what he calls ‘the most improbable project ever.’

A restless entrepreneur who grew up in New York and moved to New England, Berliner has run a Patagonia-style sustainable clothing business, a Whole Foods-style grocery and a futon business. He’s made schlocky feature films (‘they weren’t super successful’). He built a company, sold it, built another and so on.

In 2003, he and his wife Alison Jobson (who is Australian) bought 100ha at Wilyabrup in Margaret River because they loved it and wanted to retire there. The estate was virgin land (though Wilyabrup is full of illustrious estates: Pierro, Moss Wood, Cullen, Vasse Felix) and he says he had no intention of making wine; he might plant a row or two to sell the grapes.

Then he caught the bug. A friend – ‘a big New York restaurateur’ – taught him to taste and he got ‘turned on’ to Bordeaux (‘only the Left Bank’). He put himself through a night-school degree in viticulture and enology at UC Davis, and, in 2005, planted a pocket-handkerchief sized plot, one-fifth of a hectare of Cabernet Sauvignon. He was mentored at first by Stuart Watson and his father David, founder of Woodlands Wines in Wilyabrup. ‘I’m ever grateful to him. He’s brilliant and open-minded,’ Berliner says, before adding (with characteristic modesty), ‘but it took someone with my disposition and background to take it to this level.’

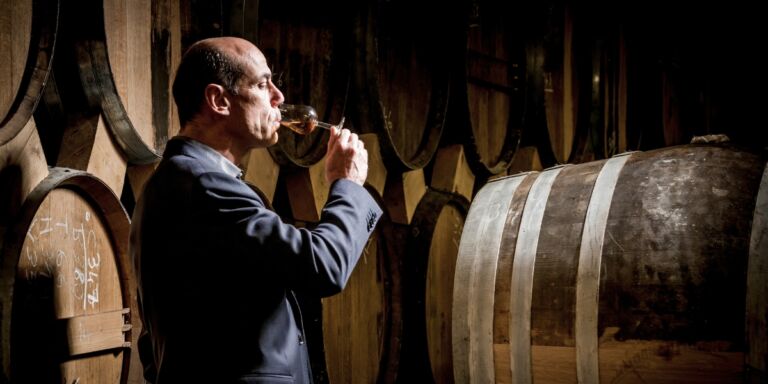

He now makes the wines himself, from a slightly bigger vineyard – 1.25ha of Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay and 10% Malbec, from which he makes hobbyist amounts of single-vineyard bottlings.

When he pours the Chardonnay, I’m expecting something pretty good but somehow not so delicate (it’s not an adjective I’d use for the stocky New Yorker sitting opposite me). There is nothing showy about Cloudburst. The Cabernet is perfumed and delicately tannin-ed, the Chardonnay restrained. They are complex, structured and elegant, the fine work of someone striving for that holy grail of sense-of-place.

It took someone with my disposition and background to take it to this level

You meet winemakers like this on every continent and each has their own way of articulating this elusive ambition. For Berliner, it’s a Gaia-like concept of oneness with the earth. ‘My life energy has always been about being in nature,’ he says. Cloudburst, he recently told a magazine, ‘is driven by very different considerations than those of my neighbours. It is cultivated differently from any other vineyard in the world.’

Over the years, he’s said a few things that might be thought foolhardy for a fast-talking American in Australia. When I put this to him, he looks for a moment like a 14-year-old unfairly accused of pinching his dad’s cigarettes. ‘I don’t know what you’re referring to,’ he says. How about the idea you’re working to a different rhythm to everyone else? This gets us into a discussion of tall-poppy syndrome, the peculiarly Aussie mechanism by which anyone who puts on airs gets quickly cut down to size. ‘I have been tall-poppied,’ he admits.

Some people in Margaret River were threatened by him, he goes on. ‘It’s a normal human characteristic for people to react in a certain way. I understand that, and part of me is very forgiving. But others realise there is great value in having an estate that’s absolutely pure and so small that it demonstrates something. And what we demonstrate is instructive for those who are willing to take a moment and listen.’

And Berliner’s neighbours seem to have got over his tall-poppyness. ‘Will nurtures the wine with his unique personality and it eventuates in Cloudburst as a unique expression of Margaret River,’ Virginia Willcox, head winemaker at Vasse Felix, told me by email. Were his neighbours annoyed by some of his comments? ‘I would hope that all growers have some different considerations to their neighbours. Will is unusually connected to his property and does things his way based on what he feels his plants require.’ The most critical I’ve heard is an off-the-record comment that ‘he’s not a team player.’

His farming methods – own-rooted, dry-grown vines, no tilling, wild-yeast ferment in open barrels, no racking or stirring – are not that unusual for a modern artisan wine, but he was ahead of the game when he planted. No-dig mulching, for example, wasn’t that much in vogue in 2005. ‘I did nothing to the soil before I planted. I put down good quality cover crops but basically all I did was poke holes in the ground and stick [in the root]. And sometimes that worked, sometimes you’d have a root that made it on top of a rock and dried up. So there’s a differential from gnarly vines to very skinny vines.’

I care about making a little bit of something extraordinary

Many gifted winemakers find it difficult to explain what they are trying to do. Some take recourse in mystical hocus-pocus, others skewer their audience with opaque science. Anyone who ever listened to the late Serge Hochar of Château Musar explaining his white wines will know what I mean.

I imagine he got into wine in the same way he got into all his other ventures: learn the subject and do it better than anyone else. But if it had been just that, he’d be farming a lot more than 1.25ha now. He insists he’s not in it for the money, and I believe him. ‘This little bit takes all of me. I don’t give a shit about scaling. I care about making a little bit of something extraordinary. And the thing that has distinguished us, for our customers, is that they get a piece of something that tastes extraordinary.’

And so he reaches for a bottle and pours me a glass that is – yes – extraordinary.