For most football fans, Ed Woodward is the man behind the hangdog expression that came to define Manchester United’s decline as he watched another defeat unfold from his perch in the directors’ box. Chief executive of the world’s biggest football club for the best part of a decade, Woodward presided over a turbulent – and, on the pitch, mostly underwhelming – period that saw the team accumulate as many different managers as it did trophies.

For Manchester United fans, Woodward was the source of deep frustration, anger and, at times, vitriol. At the height of the unrest, Woodward’s home was attacked by supporters spouting death threats. He stepped down earlier this year, after the fallout from the botched launch of a European Super League. (For the record, Woodward claims he was opposed to the concept but was using it as leverage to renegotiate the terms of the existing Champions League.)

The Woodward I meet is a world away from the popular image of the ruthless but world-weary former JP Morgan banker who prioritised United’s commercial success over performance on the pitch. ‘Timing’s everything,’ he says cheerily, by way of explanation. ‘Right now, I’m just disconnecting my brain and getting back on solid ground.’

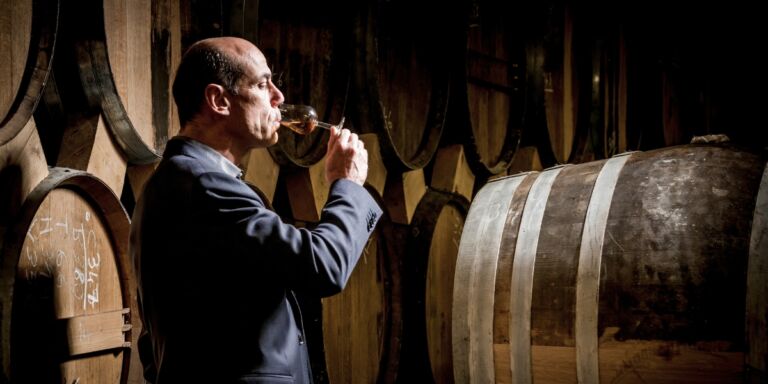

Part of that ground is in the Douro Valley, where, four years ago, he and his wife Isabelle bought a winery. And it is when talking about this that he morphs from hard-nosed financial dealmaker into a somewhat wide-eyed ingenu, his boyish enthusiasm suggesting he still can’t quite believe his luck.

Woodward’s slow-burning interest in wine dates back to an initiative instigated by his father to mark his graduation in 1993. ‘My dad worked for Ford his whole life. He was a beer man, but as he progressed in the company he was given gifts, taken for lunch, and came to like wine. He wanted me to understand wine too.’ Woodward senior funded his son’s purchase of a mixed case and told him that if he took the label off each bottle he drank and kept a scrapbook, he would ‘reload’. ‘I was a useless 21-year-old, but I did it. Not very well, but well enough that it led to more.’

Woodward stumbled into an accountancy career on the recommendation of his now brother-in-law and off the back of the ‘milk round’ corporate days that he attended ‘for the free booze’. He had met Isabelle at university in Bristol, and when they moved to London in the late ’90s, they enrolled on courses with the Wine & Spirit Education Trust in a bid to refine their palates. ‘I didn’t have any money back then,’ he says, ‘but it sent me on a journey of discovery, and that’s important.’

You don’t buy a vineyard unless you’ve got an interest in wine. We certainly didn’t buy it to make money

That journey – and its trajectory – changed in 1999, when he went into merchant banking. The bank he joined, Robert Fleming, was taken over by JP Morgan, and Woodward rose up the ranks. He recalls a vinous epiphany drinking an Olivier Leflaive Puligny-Montrachet at his boss’s house: ‘I’d never had a wine like it.’ Then there was a tasting hosted by Deutsche Bank at the Royal Academy, featuring the 1982 vintage of all five first growths. ‘I was blown away.’ The couple started holidaying in wine regions – South Africa, Australia, California. He set up a wine club with two friends, each putting in £50 a month to buy en primeur. The first vintage they bought was Bordeaux 2005 (‘We got lucky’) – the club is still going today (‘We’ve got more red Bordeaux and white Burgundy than we should have’).

That same year, Woodward was advising the US-based Glazer family on their takeover of Manchester United. After the Glazers accrued a majority shareholding in the club, they recruited Woodward to oversee its commercial operations, securing lucrative global sponsorships and doubling revenue. With his own income also bolstered, he and Isabelle started considering their own deal. ‘We’d chat over bottles of wine, and once we were on the third bottle, we’d talk about owning a vineyard – with about as much clarity as three bottles of wine permit.’

Woodward went to school in Essex with the winemaker Matt Gant, whose older brother is a lifelong friend. ‘His parents drove me to school,’ he says. Woodward kept abreast of Gant’s career as he made his name in Australia, first at mainstream Barossa brand St Hallett and then at his own more offbeat venture, First Drop. (Today he runs Gant & Co in Margaret River with his wife Claudia.) ‘Our first idea was to buy a place in Australia and have Matt run it,’ says Woodward. ‘We actually got quite far down the road with a place in Barossa, but we pulled out the day before the auction because I finally realised I was buying it for lifestyle reasons, not business reasons. And why buy a place as a lifestyle choice if you can’t visit it? That’s how muddy our thinking was.’

As Gant’s star continued to rise, he started spending his winters doing a vintage in Portugal, where he came across a young Douro winemaker named João Pires – ‘the best young winemaker I met on all my travels’. The pair hit it off, kept in touch and started sharing knowledge, Pires in the Douro, Gant in the Barossa. Gant was struck by the potential of the winery at which Pires worked, and made a mental note that it might just interest Woodward. Quinta da Pedra Alta had been owned by the same family for five generations, but illness and failed investments meant it had started to drift; it had all but stopped bottling its own wine, instead selling bulk wine to Brazil and selling most of the rest of its grapes.

In 2016, Gant invited Woodward to the Douro with Gant’s brother, a jaunt Woodward treated ‘like a lads’ trip – a pint of Guinness at the airport before the flight, that sort of thing’. He remembers Gant telling him the winery was for sale and how much it would cost, and thinking it was ‘way out of my league. I wasn’t in the position to commit,’ he says. ‘We’d bought a house near Manchester, the kids came in 2015 and I was fully into United. I still had so much to do – I was thinking I had multiple years left there.’

It was United’s first season under Portuguese manager José Mourinho, and the pressure was on. ‘The forces around United are incomparable to anything,’ says Woodward. ‘It’s easy to be CEO of a FTSE 100 company, but Manchester United was the most public private company around. It’s in the news every day. It’s full-on, 24/7, and then the games at the weekends. The longest holiday we took during my time there was five days.’

Yet despite the intensity of the day job, Woodward couldn’t stop thinking about Pedra Alta. He started to draw up plans to structure things differently, bringing in other investors. As it turned out, the sale was a protracted process in which other bidders came and went. By the time his bid was finally accepted in the summer of 2018 (for a fee negotiated down closer to that of a Championship defender than a Premier League striker), he had more money to play with and a clear five-year plan to break even.

So, what was it that appealed? The boyish grin returns. ‘Matt calls the Douro the Grand Canyon of wine regions. Did you know it represents 65% of the world’s mountainous wine regions? I remember first seeing the view from the highest point of the vineyard, at 550m, down to the river at 230m, and thinking how we could have a tasting deck there. I’m getting tingles just thinking about it.’

Again, the business element was a secondary consideration. ‘You don’t buy a vineyard unless you’ve got an interest in wine. We certainly didn’t buy it to make money.’ Mostly, though, he says, he was drawn by the people – ‘hard-working, humble; people you can work with and you want to work with’. Woodward was struck by how Pires, whose father was the hairdresser in the local village of Pinhão, could walk into any bar in the village and be greeted with ‘How are you, João?’ ‘You get that feeling of community there. I don’t have that in London.’

These are people you can work with and want to work with. Hard-working, humble… I was so impressed by how collaborative they are

In his banking career, Woodward embraced the 12-hour days and the team environment and work ethic that went with it. ‘It’d get to 9pm when someone would say, “Let’s have a sharpener downstairs and then come back to our desks and get this finished.” And everyone came, including the PAs, because they were part of a team. That’s what I’m enjoying now.

‘I’ve only been able to turn my focus to it this year, and I’m still wet behind the ears. But I’m loving learning.’ Phase one, he says, was about stabilising – ‘to keep the banks happy, reassure staff, and get everyone bought into the five-year plan’. Investments were made in a temperature-controlled cellar, grafting and replanting in the vineyard and more vats to allow for vinification of more precise parcels.

Next came a rebrand, led by Woodward’s wife Isabelle and featuring the three original granite markers (feitorias) on the property from the demarcation of the Port region in 1761.

In between times, Pires was honing his low-intervention, sustainable winemaking approach, with remote input from Gant as consultant. ‘João and I both knew this was an amazing site that just needed a fresh start, fresh energy and fresh capital to realise its potential,’ says Gant. ‘The Douro is hugely undervalued as a region. I love its diversity.’

Among the varieties planted across the 35ha site are Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca, Tinta Roriz, Tinta Barroca, Rabigato, Gouveio, Viosinho and Sousão. The variety in altitude allows for a range from aromatic whites to full-bodied reds, though Pires says renewed focus has allowed him to harness the acidity and freshness that he feels will come to define the house style.

Most strikingly, in just four years the range has grown from four to an almost unwieldy ten different wines. At the core of the range are two whites and two reds spanning a host of textures and fruit-versus-acidity balance, with the imposing, taut yet rounded reserva red ‘the long pole in the tent’, as Woodward says. The three Ports – a ten-year-old Tawny, an occasional vintage Port and a zippy white Port (unapologetically aimed at the cocktail market) – are sacrosanct, as a nod to the brand’s heritage. (While Pedra Alta was demarcated as a vineyard in 1761, it was 1998 before it made non-fortified wine.)

Like Pires, Woodward is keen to dial down the Douro power but brings a dose of realism. ‘Straight out of bottle I found our reds fruity, yes, but quite big and tannic. But we’re not [Château] Latour – we’re not going to hold on to them until they’re ready.’ Lockdown allowed for experimentation, and Clarete – a lighter, brighter red co-fermented with white grapes, intended to be served cool, and sold by The Wine Society – is, says Woodward, a way of addressing the trend to drink reds earlier. He is clear, though, that he is not telling Pires or Gant how to make the wines. ‘I’m just the dumb money.’

Woodward recognises it’s never going to be a full-time role for him (he’d like to get back into sport) – but he and Isabelle have seven-year-old twins, and in the longer term he wants his children to be involved. ‘I want them to understand the value of hard work. You look at the workers there, not earning much but picking grapes in 35°C heat on terraced schist. It’s amazingly hard work. It’s a different level of grounding. Then there’s a product to sell, across multiple countries, with duty, tax, logistics, marketing, social media… It teaches you lots of different skills, all within one small business.’

For now, he is enjoying the ride, splitting his time between London and the Douro. ‘The last time I went was during the vintage, and a few winemakers got together for a barbecue. They were sharing stories of the harvest and how business was going, and they kept running off to get this wine or that wine to taste and discuss. And there was a bunch of 18-year-old interns sitting at the end of table, not taking selfies for Instagram but talking, listening, learning. And chain smoking.

‘I was so impressed by how collaborative they all are. I’m going out there again next week, and I can’t wait to see them and have a beer with the team.’ It’s a team that, unlike Manchester United, seems to manage itself.