“Some people go to Jerusalem, others go to the Vatican, and winemakers go to Georgia. It’s the country where everything was born,” says Loïc Pasquet, the Bordeaux vigneron whose humble Liber Pater Vin de France fetches prices of about £26,000 per single bottle.

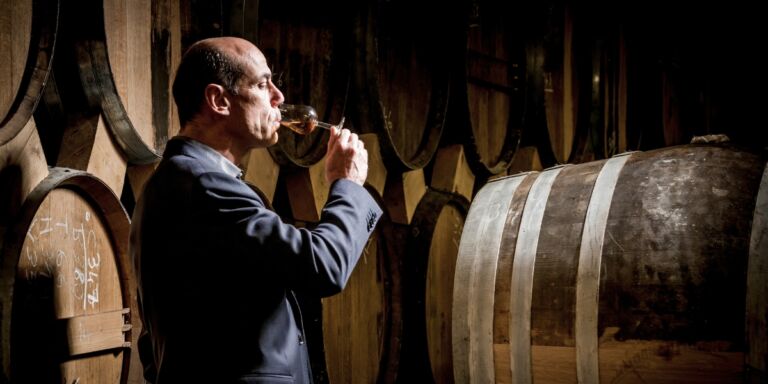

For Pasquet, these trips are now for business as well as pleasure. The winemaker has recently teamed up with leading Georgian producer Askaneli Brothers with the intent to produce fine liquid in the “cradle of wine”. Last month, he went on his own personal pilgrimage to the promised wine land, meeting with his local partners and scouting for a region, plot and grape variety fit for the project.

Although it’s still early days (“We don’t know what we’re going to do yet,” he says), Pasquet claims he is determined to champion Georgia’s long viticultural heritage – here, archaeologists have found winemaking evidence dating back some 8,000 years. He will be making the most of the country’s rich grapevine diversity, consisting of more than 500 indigenous varieties, and its winemaking traditions, including the use of traditional, UNESCO-protected terracotta qvevris as maturation vessels. But despite its heritage, Georgia’s winemaking is yet to fully recover from the impact of decades of Soviet rule.

“The Soviet Union affected both the diversity of Georgia’s indigenous grape varieties and the overall quality of wine,” says Bastien Warskotte, a Frenchman who has been making traditional-method sparkling wine in Georgia since 2017 at his own Ori Marani winery, just one-hour drive north-east from the capital, Tbilisi. “In the 1990s, right after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia went through a very difficult period with a civil war. The priority was not winemaking.”

Askaneli president and Pasquet partner Gocha Chkhaidze recalls the meagre state of the country’s wine industry at the time: “When I started producing wine in 1998, the factories were in a very poor condition. There was poor sanitation, lack of knowledge and old-fashioned bottling lines with pasteurisation.”

He says that making wine sustainably wasn’t an option with vineyards in such a bad state and with a lack of skilled agronomists, but things have been looking up in the past few years. “Georgian wine will be able to establish a high reputation very soon as increasingly good wines have appeared on the market,” he adds.

A range of exceptional Georgian wines have indeed been available internationally for some time and two of the country’s most celebrated producers, Chateau Svanidze and Khomlis Marani, have just recently landed on British shores. The former, located in the Kakheti region, has been making wine for 150 years, and sees its Mukuzani red as Georgia’s answer to Italy’s Tignanello, while Khomlis Marani, located in the northwestern Lechkhumi region, boasts a portfolio whose bottles can reach hefty price tags of about £800.

For Warskotte, the Georgian wine industry began its recovery in the mid-2000s, helped by the country’s growing economy. “Russia put an embargo on the import of Georgian wine after the 2008 war, so Georgia had to find new markets [such as] the US and Europe, therefore quality needed to increase even further.” He points out that, although the country produces wines that can age well, Georgia appeals more to the “natural” than the fine wine market.

Pasquet’s new venture, however, might be set to revolutionise the wine-drinker’s idea of the country. With his artisan approach to winemaking – he works the vineyard with a 150-year-old plough and a mule and has championed the use of amphorae-ageing in Bordeaux – Pasquet’s style should marry well with Georgia’s low-intervention approach, while bringing it to a fine wine audience.

Ronan Sayburn MS, head of wine at leading London club 67 Pall Mall, believes that having Loïc Pasquet there will draw more attention to a region that’s already on the rise in the public consciousness. “The perception of Georgian wines may have divided the [international] wine community at one point, producing orange, long-skin-contact wines without specific location or varietal differences. It may have taken some time for many in the trade to understand these wines, but they are now considered to be unique in the wine world.”

In July, Pasquet will return to Georgia to continue his quest. “The first step is to find the good terroir,” he says. “After that, we need to find the right variety that suits that terroir. Basically, in Georgia we need to ‘rediscover’ everything, as if we were Christopher Columbus.”

It’s a challenge but we will make beautiful wine, I’m sure. Georgia is a sleeping beauty

While terroir is to be confirmed, Pasquet is clear on plans to make both red and orange wines using Georgian qvevris rather than oak barrels, “but maybe with more control, because today, for instance, they don’t control the temperature.” One thing is for sure: the French vigneron is confident about the project’s potential, although he stresses that it will take time – maybe 10 years – before the first fine wine will see the light.

“Now it’s time to write a new page of Georgian wine history,” he says. “It’s a challenge but we will make beautiful wine, I’m sure. Georgia is a sleeping beauty.”