The departures board at Islay airport is not so much a list of exotic destinations, more a simple signpost. Most days, only one destination is listed from this remote Scottish island: Glasgow. The airport – essentially a café and a runway – is endearingly spartan, a flashback to how all airports used to be at the dawn of commercial aviation. Yet the baggage handler (and yes, there’s just one) on this small island off the western tip of Scotland’s Kintyre peninsula has never been so busy.

Islay is part of the Inner Hebrides, an archipelago of 35 inhabited, and 44 uninhabited, islands. For a small isle it carries incredible weight in the world of whisky. Nae, in the world of drinks. Since the turn of the century, the number of operational distilleries that call the island home has grown by 50%. Even now, this puts that number at a modest nine (soon to rise again, to 11, as we enter a new decade). But for an island of just 239 square miles – or 620 square kilometres – and a touch over 3,000 inhabitants, this is far from insignificant.

The younger distilleries, whether opened this century or the last – or indeed the previous one to that – are owned by a tapestry of international companies in France, Japan, America, South Africa and, of course, the UK. Owners and consumers alike are constantly descending on Islay from far and wide to sample its wares.

Islay has managed to take the simple ingredients of water, barley, yeast and peat smoke, and combine them into a spirit so endearing, so characterful, so flavoursome, that the whisky world is in its thrall. So much so that its house style – the signature smokiness that many drinkers often call to mind when they think of Scotch – is the fastest growing style of whisky purchased globally today. But what is it that makes this island’s rendering of a single malt quite so compelling?

Ultimately, it’s all down to the terroir. The island is abundant in peat bogs, which for centuries have provided the locals with fuel – for a peppercorn rent, residents can dig up and burn as much of this ancient earth as they need. The peat, when lit, releases a delightfully aromatic, earthy tone, which gently rises from the chimneys of the island’s houses. It also provides the key component to dry the barley used in local whisky production, to which it also lends its pungent smoky aroma. The result is a whisky with real character, setting the island’s spirit apart from the more delicate notes found in Scotch on the mainland.

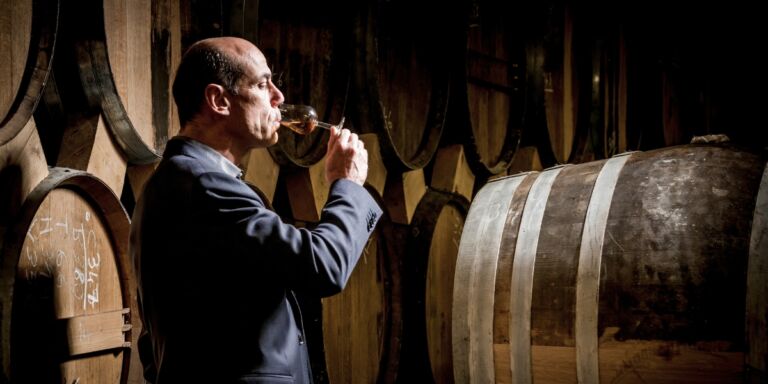

Once out of fashion as undrinkable whiskies from unpronounceable distilleries, these smoky Scotches have recently found global success, garnering a hardcore fan base and finding their status rising to the realms of luxury. Consider the eponymous distillery located in the island’s main village of Bowmore. The current flag-bearer for high-end, luxury Islay single malt, Bowmore distillery dates back to 1779 and its coastal warehouses are home to the oldest stocks of single malt whisky on the island – and the most sought after whisky releases of the past decade. Such stocks were captured in a 2012 release of a 54-year-old 1957 vintage, the oldest bottled Islay single malt ever to hit the market. This was followed by a 50-year-old 1966 vintage in 2017 and the following year by a 52-year-old 1965 vintage boasting a price tag of just over £22,000.

Amid such eye-watering price tags, it is perhaps no surprise to see Bowmore announce a partnership with luxury car maker Aston Martin. The collaboration will see the two British brands create an exclusive series of products and experiences, as well as rare and unique bottlings.

A short drive east from Bowmore, past the ever-busy airport, is another coastal village, Port Ellen, which since 1983 has been haunted by a ‘ghosted’ distillery. Port Ellen distillery was one of a number of malt whisky producers that fell silent in the early part of the 1980s, a victim of a global contraction in demand for Scotland’s liquid gold. This decade of doom saw distilleries such as Brora, in the far north east of Scotland, just 60 miles from John o’ Groats, down to Rosebank 250 miles further south, and across to Port Ellen on Islay, lock their gates and silence their stills. As each was deemed surplus to requirements, their buildings were left stripped and empty, as mere monuments to an industry’s past glory – save for the stocks of Scotch lingering from generations past.

The twist in the tale saw these slumbering stocks of single malt improve dramatically over time. And as releases from these closed distilleries started to be opened, the reviews were not just great, but fantastic. Leading the critics’ charge was Port Ellen, whose old stock was released in small annual batches by owner Diageo. A frenzied secondary market developed for these rare releases, and finally a move by Diageo to reopen the distillery was announced in 2017 – albeit on a much smaller scale than in the old days. Planning permission was granted in early 2020 and the distillery should restart production in 2021.

Port Ellen won’t be the first Islay distillery to rise from the ashes. Ardbeg was closed from 1981 to 1989, before returning to full production after being bought by the luxury goods company, Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy. The distillery sits at the far end of a run of three famed Islay producers who call the south eastern coast their home.

Perhaps the most famous of these is Laphroaig. Almost a household name, its 10-year-old expression, with a white label and sporting a royal warrant, is a staple of back bars the world over, and is often many drinkers’ first experience of the smoky Islay style. With a focus on a distinctively bold, medicinal flavour, Laphroaig has many fans, and as a result, stocks of aged Laphroaig are rare, often topping out at 25 to 30 years old. A bottle of Laphroaig that carries an age statement over three decades is as coveted as a spare seat on the small aircraft in and out of the island – the last major offering was a limited-edition 30-year-old, with a sister bottling at 25-year-old, both released at the tail end of 2019 for just under £1,000 apiece.

The final name in this holy trinity is Lagavulin. Another distillery with a following that would walk over the hot ashes of smouldering peat to obtain limited-edition releases, its style of single malt is still undeniably peaty, yet more subtle than neighbouring Ardbeg or Laphroaig. Lagavulin’s best-known bottling is a 16-year-old. It’s a whisky that you can’t imagine ever not being there. Having such a classic release as Lagavulin 16-year-old means that the distillery does not rely on extra-rare releases to appease its growing fan base. An annual 12-year-old limited edition has been a regular appearance for Lagavulin fans over the past decade, and recent additions of an eight-year-old and 10-year-old have bolstered the core range. Yet on the rare occasion when a limited-edition Lagavulin with real age is released, it causes some flurry indeed. In 2017 a 24-year-old 1991 vintage was released for charity, selling out in record time, even with a price tag approaching £1,500 per bottle.

Perhaps the most heart-warming of all the stories on Islay is that of Bruichladdich. One of the five distilleries in the north of the island (along with independently owned Kilchoman in the north west, and the workhorse of Caol Ila, the diffident Bunnahabhain, and the new kid on the block, Ardnahoe, all based on the north east coast with views out to Jura), it epitomises the island’s renaissance.

Its history is as rough as the sea it overlooks. Founded in 1881 by the Harvey brothers, Bruichladdich was a quiet operation producing mostly single malt for a variety of blending houses. From this bright start, the distillery lost its way, with eight different owners in just over a century before finally, in 1994, being mothballed. That Bruichladdich didn’t become a ‘ghost’ distillery was thanks to two parties: the locals, for whom the slowly fading whitewashed distillery walls always remained a bright beacon of hope; and London-based vintners Simon Coughlin and Mark Reynier who, in 2000, relocated to Islay and led a consortium – including key local landowners – to purchase the site and its remaining stocks.

Adding the former manager of Bowmore, Islay whisky-making legend Jim McEwan, to the team, the new owners forged ahead with a programme of reinvestment, and a heavy focus on using local ingredients, with local talent, and extreme levels of provenance. Today, all the various expressions of Bruichladdich whisky – whether traditionally unpeated, smoky (as in Port Charlotte) or heavily peated (Octomore) – are distilled, matured and bottled on the island, using 100% Scottish barley and reflecting only the natural colour that comes from the casks.

As a result, Bruichladdich has become Islay’s largest private employer, opening a bottling line that employs most of the local elderly and disabled workers. Sourcing casks from some of the top-grade vineyards across Europe allowed the team to enhance the quality of existing mature stocks, and nearly a decade after reopening, Bruichladdich became part of the family-owned French company, Rémy Cointreau.

With stories such as this, and whiskies of real quality being released across the island, it’s no wonder that Islay, and its whisky community, is buzzing right now. As it continues to thrive, one hopes it won’t lose the unspoilt, elemental nature that makes it so special. But perhaps, in time, the resident baggage handler will recruit a colleague…