In late 2025, the East London Liquor Company (ELLC) released a blended whisky consisting of its own aged stock and spirit from Loch Lomond distillery. Called East London Threads, it’s the first whisky made under a new business structure that sees the company adopt a nomadic production model.

This was quickly followed by news that the former Chase Distillery (which had seen its production moved to Scotland after a sale to Diageo) was to be reborn as Rosemaund Distillery, with its stock of whisky bought back into family ownership on the farm where it all began. Its first release, a 10-year-old single malt, was launched just a couple of weeks later.

Meanwhile, Scotch distillers, masters of romanticising their roots, often use grain from the other side of the country, distil on tiny islands, then ship casks to mature on the mainland. It’s not unheard of for spirit to be blended far away in the headquarters of their multinational owners too. So, does place matter in whisky or is it just marketing? And what does it really mean for a whisky to be ‘from’ somewhere?

A nomadic approach to whisky-making

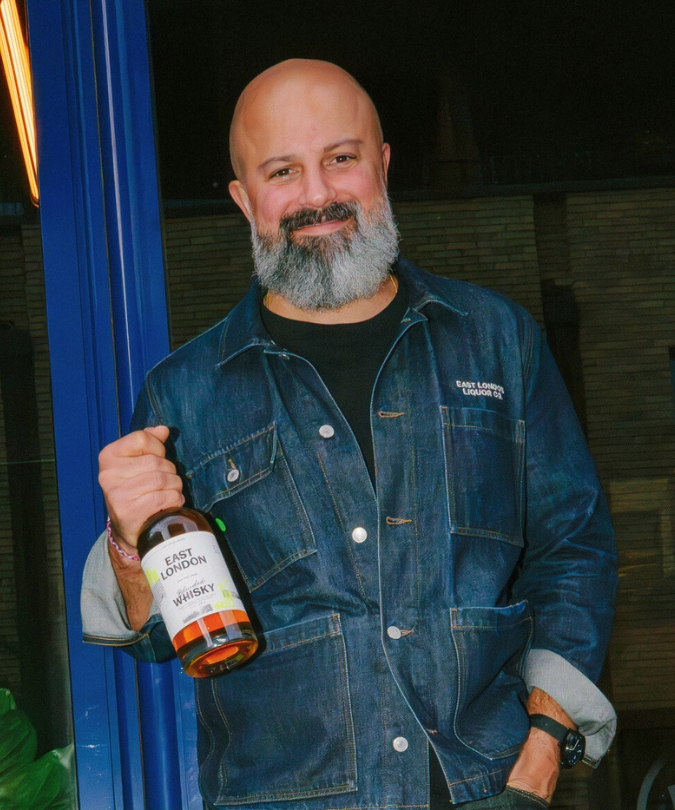

‘Terroir in whisky is based more on the decision-making and technique of the staff,’ says Alex Wolpert, the ELLC’s founder. For him, these human factors outweigh where a spirit is made or what sort of still is used. ‘It’s a far less romantic story but probably more accurate,’ he says.

By late 2023, the ELLC had been laying down spirit for close to a decade at its home in Bow. Hundreds of barrels of whisky were maturing in its warehouses and, for a small indie brand, that was more than enough. ‘Even based on some pretty bullish forecasts, production of more whisky wasn’t at the forefront of my mind,’ Wolpert says.

More pressing concerns centred around the rent, which had ballooned to almost a third of the distillery’s operating costs. Six months of conversation with the landlord made it apparent they couldn’t make the numbers work. The business was restructured and Wolpert began looking for a new site.

Wolpert’s ethos is not defined by where the whisky is made but how and with what

Replicating its home in Bow felt impossible, which led Wolpert to question what mattered most: was it to have everything in one place but leave East London, or was it to maintain a presence – however minimal – in the area that Wolpert calls the brand’s heartland?

Wolpert landed on something rare in whisky: a nomadic approach. ELLC would keep a home in East London and start releasing its aged whisky from there but distil elsewhere. ‘What East London stands for transcends place,’ Wolpert says, adding that his ethos is not defined by where the whisky is made but how and with what.

The ELLC is not alone in making this break with the stillhouse. Fielden began life as The Oxford Artisan Distillery with a strong focus on sustainable agriculture, though – as sales & marketing director Hannah Groom is the first to recognise – this sometimes got lost in the messaging. When it finally outgrew its Oxford site (a Grade II-listed barn on a former farm), there was a natural opportunity to rebrand and focus on what the company wanted to convey: that the fields matter most. Fielden literally means ‘of the fields’.

Finding a new distillery site proved prohibitively expensive, so they decided not to proceed with one. ‘We realised that having another fixed site would probably detract, again, from the message that we’re trying to convey,’ says Groom, adding that many distilleries are secretly nomadic; buying barley farmed far away, distilling in one place and maturing in another. ‘In that sense, we’re not so different,’ she says. Fielden’s new-make spirit is now distilled with Adnams in Southwold.

Growing grain: focusing on how not where

Fielden currently only sells rye whiskies, though it is distilling and laying down spirits made from other grains. Its Signature Expression is blended to be consistent from year to year but its other lines do the opposite. Its Harvest Release series, for example, celebrates crops from specific years: 2019 and 2020 are currently available.

This focus on rye boils down to two things, the first of which is that they like the flavour. The second is that Fielden advocates ‘no chem regen’, which means growing grain without any fertilisers, pesticides or herbicides.

The idea of place in whisky is surprisingly malleable

By adopting this model, Fielden is not saying place doesn’t matter. Rather, that the place that matters most is where the grain is grown – and as a result, society should do more to look after it. ‘With regenerative farming, the ambition is to leave the soil in a better condition year-on-year than you found it,’ says Groom.

Groom says that if conventional farming continues as it is today – disturbing the soil, relying on chemicals and fertilisers etc. – it won’t be long before the land is too depleted to grow enough grain for food, let alone alcohol. There may be as few as 30 or 40 harvests left.

From grain to glass in one place

Unlike the ELLC or Fielden, Rosemaund is a farm distillery. Everything there from grain to glass happens in the same place, so it’s little wonder they emphasise the importance of place. The team there farms its own Maris Otter barley. It’s good for soil health, Rosemaund founder James Chase tells me, as well as flavour. They distil the whisky on the farm and age it there too, in warehouses made from old potato barns that are now nicely racked for health and safety, thanks to investment from Diageo.

Chase believes it’s the warehousing stage that matters most. ‘If I was to hang my hat on a production element, I would definitely say that where those casks are aged is fundamental to flavour.’

The warehouses sit right next door to apple orchards. ‘That meadowsweet, baked-apple flavour that you get [in the whisky], I really think that’s coming from the flora, the fauna, almost the atmosphere where those casks are aged, flanked by apple orchards,’ says Chase. It may sound romantic but he’s right; you can taste their influence in the whisky.

Chase tells me he bought a few casks of 2008 Glenrothes that were made and filled in Scotland but immediately shipped south to the warehouse on Rosemaund Farm. This allowed Chase to do a little compare and contrast; a side-by-side tasting of the same whisky from the same casks but aged in Glenrothes or in Herefordshire. Chase says the differences were huge and amazing. ‘You’re still getting this Glenrothes element of banana, lemon and lime peel but the meadowsweet and baked apple taste that you get from [maturing the casks at] Rosemaund is so present as well.’

Island influence

Not every Scotch distillery is a multinational operation spread out across the country. At the Isle of Raasay Distillery (suitably small for such a decidedly wee island), founder and head distiller Alisdair Day also runs a compact operation. He shares Chase’s belief that it’s where the spirit matures that matters most.

He points out that the mashing, fermenting and distilling is over in a matter of weeks, whereas maturation takes at least three years and usually much longer. Raasay’s maritime climate means it gets neither too cold nor too hot, and it gets a lot of rain, so the humidity in the warehouses remains high, particularly from October to April. ‘Ideal conditions for maturing Hebridean single malt Scotch whisky,’ he says.

The idea of place in whisky is surprisingly malleable and is not as simple as where the stills are. If place matters to a whisky at all, it’s the influence of land and climate on the grain as it grows, the casks as they age, and the minds and choices of the makers.

Perhaps there is no definitive answer. Perhaps, ultimately, a great whisky suggests what matters most on its own terms and then makes an interesting argument, and a pleasurable dram, out of trying to convince us that it’s correct.