Mouton-Rothschild’s legendary labels and the forgotten artist who launched them

Seventy-five years ago this month in Bordeaux, as the Allies celebrated the end of the Second World War, a fine summer was moving into a fine autumn. With everyone keen to embrace some form of normality, harvest was underway.

After the chaos and tragedy of the war, the 1945 vintage was considered a mini miracle. The vines had been blighted by frost and snow in May, but they enjoyed a hot and dry summer and an uncomplicated harvest. Enduring wines were produced by all the great estates that year, though Mouton-Rothschild – then a lowly second growth – produced a wine of brilliance. Mouton 1945 is one of a handful of wines that sit in an iconic class of their own. A bottle sold at the recent Zachy’s London auction for £9,920 – many wines fetch more, but few have the romantic lustre of the ’45.

To mark that wonderful harvest, the owner of Mouton, the charismatic Baron Philippe de Rothschild, commissioned an unknown young designer, Philippe Jullian. His brief was to produce a label that would represent a new beginning and celebrate the end of war.

Philippe Jullian

The story of the Artists’ Series of labels of Mouton-Rothschild is well-known. The story of Jullian, he of that legendary 1945 label, is seldom told. Jullian is celebrated among the few cognoscenti of Symbolism and mid-20th century graphic design, but that’s about all. While the Mouton commission would have been a mere moment in his long career, his history and that of the great Médoc chateau are inextricably entwined.

The young Baron Philippe was born in 1902 and brought up in Paris. When the Germans looked like seizing the city in 1914, he was evacuated to Château Brane-Mouton, the Bordeaux property his great-grandfather had bought in 1853. He liked life on the estate, and in 1922 he took over its administration and began take its marketing more seriously. In 1924, he commissioned the designer Jean Carlu for a striking, one-off Art Deco label.

In his determination to push Mouton’s reputation (when the 1855 classification was issued, Lafite, Latour, Margaux and Haut-Brion were decreed firsts while Mouton topped the list of Seconds – it was finally promoted in 1973) he borrowed a ruse from his Lafite cousins and insisted on château-bottling. He even splashed it on the label: “The whole harvest has been bottled at the château.” He was joining a very small club of properties that could sell at the highest prices.

The Carlu label was a demonstration of the Baron’s aesthetic sensibilities. He raced cars, made films and wrote books. He married Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure, by whom he had had a daughter while she was still married to her first husband. A second child died in infancy and the marriage broke up soon after. When the Germans occupied France in 1940, it wasn’t good to be Jewish, or a Rothschild. Mouton was sequestered by the Germans and Baron Philippe and his wife were arrested. The baron escaped and made it to England to join the Free French. Elisabeth fared less well. She was taken to the Ravensbrück concentration camp where she died in 1945, probably of typhus, the only Rothschild to perish in the war. Their daughter Philippine, born in 1933, survived and went on to inherit the estate on the death of the Baron in 1988.

Baron Philippe de Rothschild

Perhaps the Baron’s greatest legacy is the Artists’ Series. As with many design classics, Jullian’s 1945 label is simple: a band of white, decorated with vine leaves, a laurel wreath denoting triumph and glory, a Churchilian V for victory, and the words “1945 Année de la Victoire.”

For Jullian, the Mouton commission was a mere moment in a long career as (Wikipedia puts it best) an “illustrator, art historian, biographer, aesthete, novelist and dandy.” Born in 1919 to a prominent family of Bordeaux intellectuals, “he was a last and lasting example of pre-war camp,” writes the British graphic artist John Coulthard. “His career began as an artist in Paris with a reputation for drag-acts parodying English spinsters.”

From the end of the war to his death in 1977, Jullian moved between Paris and London, collaborating with a wide variety of artists and writers. He designed a series of covers for the fledgling Penguin books – mainly Henry James and CP Snow – and illustrated volumes of Balzac, Dostoevsky, Oscar Wilde, Proust and Vita Sackville-West. With his Dreams of Decadence he is credited with re-launching the Symbolist movement that had started in the 1890s, with Edgar Allen Poe among its prime movers. Jullian wrote biographies of Sarah Bernhardt and Oscar Wilde. Many of his works are held in London’s Victoria & Albert museum.

His end was lonely and tragic. He was deeply upset by the 1972 death of his friend Violet Trefusis (a key member of the “Bloomsbury Set” of writers and artists, and inspiration for Virginia Woolf’s Orlando) and devastated by a fire in his apartment in which many of his pictures were lost. Then in 1977 his Moroccan servant and companion was stabbed to death. Five days later he hanged himself.

Coulthard adds a final note: “In his autobiography, La Brocante [1975], he not only announced that he would take his own life, but hoped his ashes would be auctioned, in a celadon pot from his motley but fascinating collection of bric-a-brac, to unsuspecting buyers at the Hôtel Drouot Paris’s great auction room.”

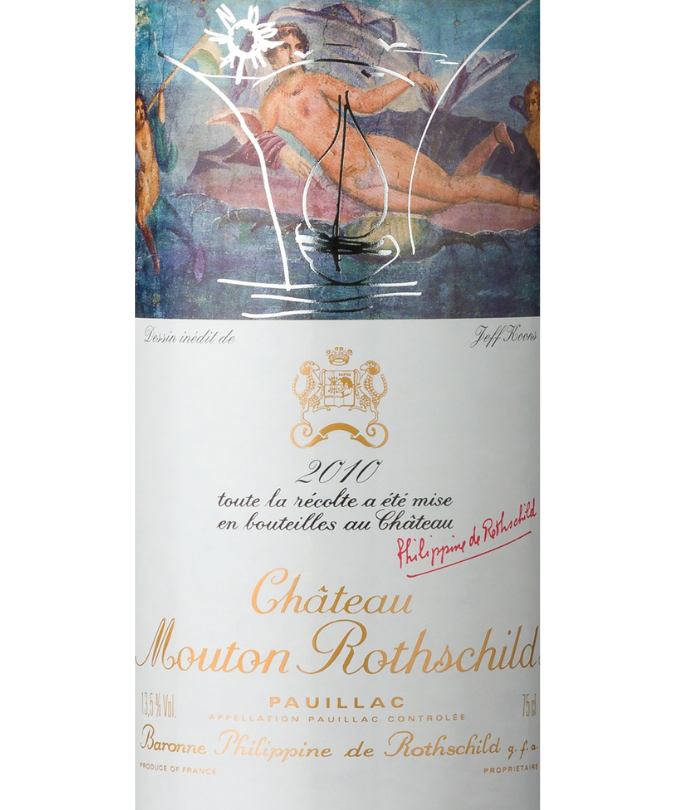

Jullian might be a footnote in the history of art, but his 1945 label started a great tradition. The Baron, followed by his daughter Philippine and, on her death in 2014, her sons Philippe Sereys de Rothschild and Julien de Beaumarchais, and their sister Camille Ögren, have attracted – literally – every significant artist of the last 70 years. Henry Moore, Miró, Chagall, Braque, Picasso, Warhol, Francis Bacon, Dalí, Balthus, Lucian Freud, Jeff Koons, David Hockney; the Korean artist Lee Ufan and China’s Xu Lei and Gu Gan. Even royalty has contributed – Prince Charles designed the label in 2004.

Adam Lechmere

Jean Carlu was born in 1900 to a family of architects (his brother Jacques built the Palais de Chaillot in Paris). He specialised in poster design from an early age, and despite losing his right arm in a motor accident in 1918 (on the very day he was named Designer of the Year by a panel of judges headed by the famous graphic designer Cappiello), he went on to become one of the most influential graphic artists of his age. He was politically active, contributing to the peace movement and the struggle against Nazism. He was influenced by Cubism – as can be seen in geometric lines of his 1924 label – and Surrealism. He lived in the US from 1940 to 1953, and died in 1997

“Illustrator, art historian, biographer, aesthete, novelist and dandy”: Philippe Jullian, the designer of the now-legendary 1945 label, which kickstarted an annual guest artist for Mouton’s grand vin, led a troubled life, as detailed above

Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) is regarded as one of the greatest – and most controversial – surrealists. Born in Catalonia, where he lived for the rest of his life, his work was by turns humorous, mystical, horrific, erotic – or the wildest fantasy. The self-proclaimed genius produced an image for the 1958 vintage that “has all the innocent charm of a child’s drawing,” the château says.

Joan Miró (1893-1984) was, like Dali, a Catalan by birth, but moved to Paris in 1919. His unmistakable style is seen in the 1969 label, the château says, via “a world of violent colour, shapes and symbols and vaguely alarming insects, but full of the light and innocence of childhood.” His drawing includes a respectful nod to the family: the blue and gold of the Rothschild racing colours

The Picasso label is unique in the series for not having been commissioned: the artist had died that year. For this most significant of vintages – it was the first that Mouton released as a First Growth, having been elevated that year – the Baron applied to the Picasso family for permission to use a 1959 painting already in his collection. It is titled, fittingly enough, “Bacchanale”. All the labels are inscribed with the famous motto, Premier je suis, Second je fus, Mouton ne change (First I am, Second I was, Mouton doesn’t change). The last three words, handwritten, appear again in 2015, the first commission made after the death of Philippine de Rothschild in 2014

Andy Warhol (1930-1987) defined Pop Art as “the art of making the ordinary original”. For the 1975 label, working from photographs, he juxtaposed two images of Baron Philippe. On the left, the Baron looks quizzically – even wryly – out at the world; on the right, he’s in repose. He might almost be asleep in bed, though as you look closer it’s clear he is wide awake, not dreaming but thinking

Keith Haring, who died in 1990, was much-loved for the innocence and joy of his deceptively simple line drawings. One of the best-known artists of New York’s East Village, he avoided what he saw as the elitism of the art galleries and focused on “public works” – inner city graffiti and his “Radiant Child” in lights in Times Square. His 1988 label – no more than a few lines and circles – is a delight. The conjoined rams (a nod to the Rothschild coat of arms) appear to be dancing; although, depending on your point of view, the image could be two human figures carrying ram devices (shields, or masks?) taking part in some kind of ritual. It’s a charming drawing

Instantly recognisable as Francis Bacon, this image was created by the artist some 18 months before his death. Bacon continues to capture the imagination – a never-shown canvas from a private collection came to light in 2016 and immediately made headlines. “Study of a Bull, 1991” shows the animal backing tentatively from light into darkness – critics are unanimous that is is the almost unbearably poignant work of an artist who knows he is dying. The Mouton label, a dancing figure with a glass of wine, is in its way just as moving

Balthus (Count Balthazar Klossowski de Rola, 1908-2001) was a compelling figure, throughout his life attracting the admiration of artists and writers from Rainer Maria Rilke to Giacometti, Fellini to Camus. He painted portraits, landscapes, streets, all “transfigured by an instinctive feeling for the secret life of people and of things,” the château says in its introduction to the artist of the 1993 label

Lucian Freud, who died in 2011, was the grandson of Sigmund Freud and member of a family that is prominent in the artistic and cultural life of Britain. He was an extraordinary personality – hugely talented, driven, venal (it’s uncertain how many children he had), reckless and selfish, both loyal to his friends and occasionally brutal, a friend of Francis Bacon (their Soho drinking bouts were legendary) and lover to countless of his models. Now, a decade after his death, he continues to fascinate, not least because the critic William Feaver, who spoke to him daily over a period of some 30 years, has just published the second volume of his The Lives of Lucian Freud.

The 2006 label is a departure for a painter who dealt almost exclusively in portraits. You feel he’s as delighted by the commission as his (Spanish?) zebra is by the potted palm it’s thrust its head through the window to investigate

Jeff Koons is a leading figure in contemporary art, best-known for his steel sculpture Inflatable Rabbit (1986); his 12m, 16 tonne Puppy, the flower-bedecked dog that guards the entrance to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao; and for his marriage to the Hungarian-Italian porn star and politician with whom he created Made in Heaven, a series of astonishingly graphic giant photographs of the pair in full sexual congress. The heir to both Duchamp and Warhol, Koons is endlessly inventive and provocative – his 2010 label revisits the Birth of Venus, the famous fresco from Pompeii

The German artist Gerhard Richter’s amorphous, harmonious abstract “Flux” marks a watershed for Mouton: it is the first label to be commissioned by the three children of Philippine de Rothschild, the much-loved matriarch of the property, who died in 2014. There’s a poignant juxtaposition between label and artwork: the title of the latter, Flux, signifies movement and change, which is indeed what has happened at the great old property. But Philippe Sereys de Rothschild signs the label on behalf of his siblings with the famous motto, “Mouton ne change”.