Wine

The grands crus of Bordeaux in the summer of ’69

Photography by Peter Aaron

Peter Aaron was 23 when he was commissioned by Alexis Lichine, the legendary wine writer and owner of Château Prieuré-Lichine, to provide photography for his latest book on the grands crus of Bordeaux. Aaron is the son of Sherry-Lehmann founder Sam Aaron (‘My father was a big deal in the wine business,’ he says matter-of-factly), but this was only the second time he’d been to Bordeaux. In the summer of 1969, he stayed at Château Bouscaut in Pessac-Léognan, and spent a month and a half in the vineyards and chais, photographing the everyday life of the great properties.

The pictures vibrate with life – you can almost smell the baked earth and the rich perfume of newly harvested grapes. This was half a century ago, but it’s by no means a vanished way of life: workers still gossip over the sorting table, there are horses in the vineyards again, and barrel design hasn’t changed in 3,000 years, let alone 50.

This is a cross section of Bordeaux, every rank from picker to maître de chai. ‘What was memorable for me was capturing the average worker in the vineyards,’ Aaron says. ‘The picture of the shepherd woman in traditional dress with her staff and her dog, at Yquem, is one of my favourites.’

Aaron is an acclaimed architectural photographer whose work is in high demand. He worked at Time-Life in the 1960s, training under the great architectural photographer Ezra Stoller, whom he consistently names as one of his major influences.

The Bordeaux series was shot on a Nikon F camera, almost entirely in black and white, which Aaron says he favoured over colour. ‘Looking back 50 years, black and white seems timeless,’ he adds. In the event, Lichine never finished his book. The pictures were published in issue 3 of Club Oenologique for the first time; apart from a show at the Alliance Française in New York in the 1980s, they have never been exhibited.

Adam Lechmere

The steep, narrow streets of Saint-Emilion look a touch smarter nowadays, with boutiques and cafés catering for the thousands of (pre-Covid) tourists that flock to a town so historic it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999.

At Château Haut-Brion, a cellar worker purifies an empty barrel with a chip of burning sulphur

A similar process at Château Ausone: lighting a sulphur wick on an acetylene lamp. The wick is attached to a wire which is fixed to the bung of the barrel. When the bung is replaced, the wire ensures that the wick burns in the middle of the barrel, without the flame touching the wood.

At Château Graysac, north of St Estephe, a horse is protected from flies with a hood that might almost have been crocheted by the driver’s grandmother

Pruning the vines at Château Pichon-Longueville-Baron. The cuttings – sarments – made excellent fuel for grilling côte de bouef

Well-equipped with parasol and folding stool, a local shepherd and her dog at Château d’Yquem

Horses were a feature of vineyard life in the 1960s, as seen at Saint-Emilion Premier Grand Cru Classé Château Clos-Fourtet. Today, as sustainable viticulture becomes more and more prevalent, they’re once again a common sight at many properties

Racking – or soutirage – at Haut-Brion

Château Haut-Brion. The perspective, through sun-drenched vines, makes one of the grandest properties in Bordeaux look like twee little castle in a fairytale

Two images of perennial labour at Château Latour. Tractors have evolved, as have the vineyard workers’ clothes, but those details apart, this sort of work among the vines remains much unchanged today

Château d’Yquem cellar master Roger Bureau (whose nickname – unsurprisingly – was “Moustache”) poses with quiet pride in front of wooden cases stamped with the then-owner’s name. Comte Alexandre de Lur-Saluces had taken over the great Sauternes estate only the year before, on the death of his uncle, Marquis Bernard de Lur-Saluces. He was to run the property for the next 30 years, until it was sold to the LVMH empire in 1996 after a vicious internecine feud. The family had owned the château since the end of the 18th century

The great Alexis Lichine, with daughter Alexandra and son Sacha. Lichine commissioned Peter Aaron’s photographs for his book, which in the end was never published (see Introduction). Today Sacha runs Provence estate Château d’Esclans of Whispering Angle fame

Corking at Lichine’s Château Prieuré-Lichine. Some things do change – hand-operated corking machines were already on their way out by 1969

Barrels at Château Ausone, the ones in the foreground looking decidedly the worse for wear. Winery practices have become vastly more rigorous in the last 50 years, but even in 1969 barrels in this condition would have been good for nothing but scrap

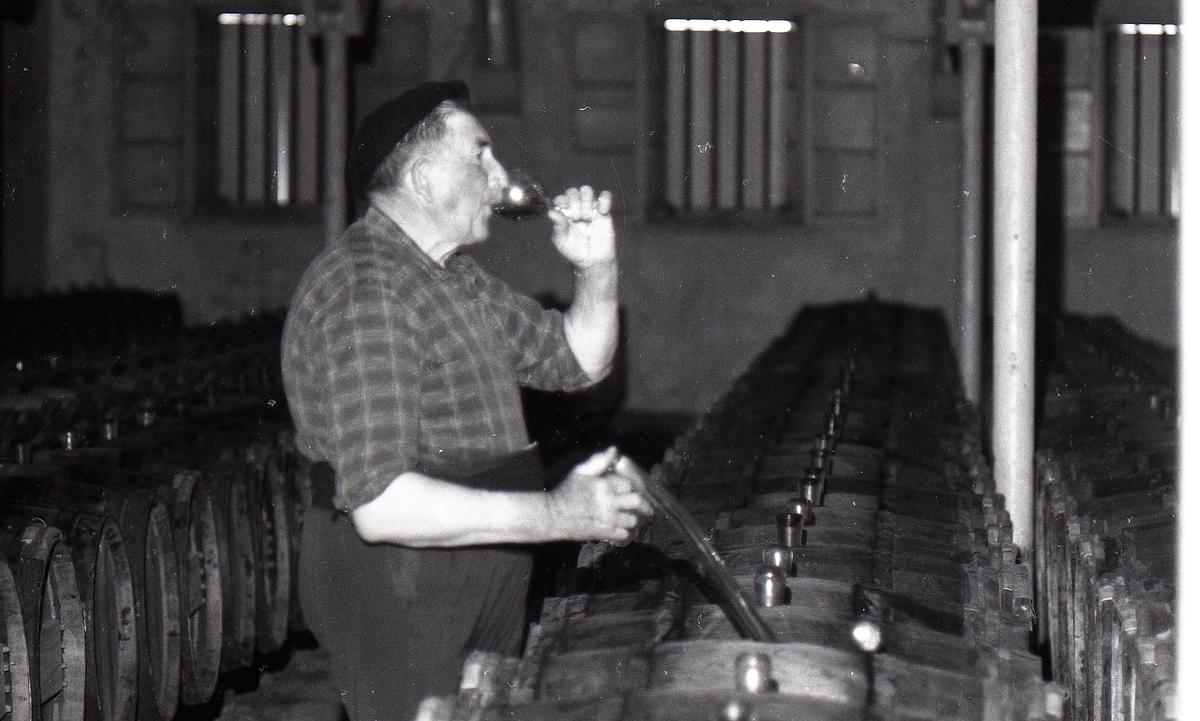

Cellar master Roger Bureau (aka “The Moustache”) tasting from barrel at Château d’Yquem

At Château Lascombes in Margaux, a hay wagon sways along, the texture of the hay echoed in the luxuriant vines and the deep ivy that covers the walls of the house. You can almost smell the sun-baked grass, and hear the slow clop of the horse’s hooves

Howard Sloan, then-owner of Château Bouscaut – where Peter Aaron stayed in the summer of 1969 when these photos were taken – with wife Sonny and daughters Kathryn and Gillis. Sloan had headed the American syndicate which had bought the property a year previously, and this is one of Aaron’s favourite images of the series. “It’s the most beautiful vineyard in Bordeaux,” he proclaimed.

Sloan with the cellar master at Bouscaut

A pair of hunters and their dog among the vines in Pauillac. Further south, in the hilly, forested Languedoc, they would be after sanglier (wild boar). In Bordeaux, rabbits and crows

Jean-Bernard Delmas at Château Haut-Brion. Delmas, who died in 2019, was technical director at the first growth from 1961 to 2003. He succeeded his father Georges Delmas, and is in turn succeeded by his son Jean-Philippe.

William Bolter, negociant, in a photograph so perfectly theatrical that it could be a still from a play

Wrapping bottles at Château Climens – another timeless scene. Many of these workers would have been the sons and daughters of people who carried out similar jobs a generation before; many of their children and grandchildren will likely still be working, and gossiping, at Bordeaux châteaux today