It’s a wet Friday morning in January. Driving through Napa Valley, I’ve had to adjust my route to avoid the flooding. The Napa River has burst its banks after record winter rainfall, and vineyards across Rutherford and Oakville are underwater.

As advised, I’m wearing rubber boots. I’ve also donned my thickest work trousers and layered on the winter clothes. It’s an incongruous look given that I’m on my way to one of the most exclusive, revered California wineries – indeed, the world. But today there will be none of the chic drinks receptions and hobnobbing on the expansive terrace that are so prevalent in Napa wine society, not least because this particular winery doesn’t really have a terrace. In fact, from the road, there’s barely any indication of a winery at all: no grand gates, no flashy flags, no showy signage – just a gatepost displaying the number.

I’m here to get a look inside Screaming Eagle, discreetly set off the Silverado Trail on the eastern side of Oakville. It’s one of the most difficult wineries in the world at which to secure an appointment. (Jay-Z was famously rebuffed when he made an approach.) Many of the world’s top sommeliers have been turned away, along with several of the wine world’s top publications. They haven’t given an in-depth, on-site media interview in several years.

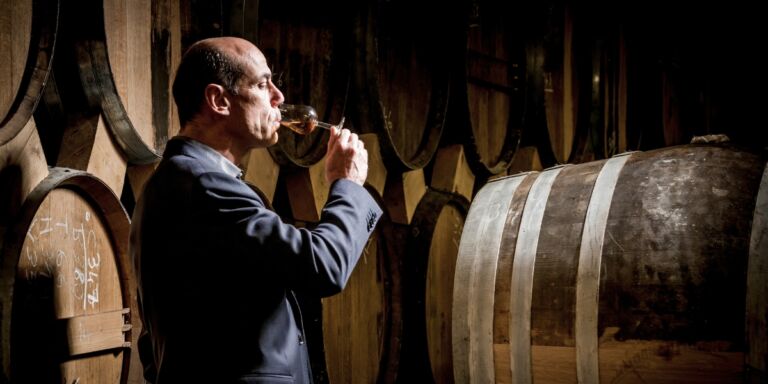

Nick Gislason, the winemaker here – and the man behind the rubber-footwear counsel – greets me holding his daily mug of chicken broth, looking like a 1970s beatnik, with his oversized jacket and unruly, curly hair. Unassuming and quietly spoken, Gislason is dressed in the dark workpants and wool layers more typical of life in the Pacific Northwest than one of the most prestigious wineries in the world. We slowly begin walking the vineyard.

Winemaker Nick Gislason greets me holding his daily mug of chicken broth, looking like a 1970s beatnik

Gislason has led the winemaking team at Screaming Eagle since the notoriously cold and wet 2011 vintage. At the time, the appointment of the young winemaker by owner Stan Kroenke was seen as a surprising choice. Gislason had earned his master’s in viticulture and oenology from UC Davis but had otherwise done only short stints at a few choice wineries – Harlan in Napa Valley and Craggy Range in New Zealand among them – before a year as assistant winemaker at Screaming Eagle. Kroenke’s more high-profile role includes the ownership of top sports teams around the world, including Arsenal Football Club and the Los Angeles Rams of the nfl. He saw the young Gislason as the equivalent of his first-round draft pick, a means of identifying new talent common to the business for which Kroenke is better known. And his pick worked.

For anyone else, 2011 could have been an inauspicious start at such an iconic winery. It was one of Napa’s more challenging growing seasons, a shockingly late harvest brought on by persistently cold temperatures and punctuated by rain. Winemakers all over the valley cursed the season. But for Gislason, who grew up in the San Juan Islands of Washington State, where proximity to the cold Pacific Ocean ushers in some of North America’s most steady rain, the vintage felt almost familiar. The wines he made that year were among the top rated of a difficult vintage – or any vintage. Antonio Galloni of Vinous gave Screaming Eagle 96 points. Gislason’s subsequent vintages have garnered even higher scores.

When I taste the 2011s later, I find that they have aged beautifully, deepening their tones to an earthier hue while retaining a firm and fine-boned structure. For now, as we walk the vine rows on this wet morning, I have a more tangible exposure to that earthy feel, as evidenced by the mud adhering to the bottom of my boots. But nowhere is there standing water. This sloped vineyard’s rocky soils make for better drainage than many of its neighbours. And unlike excess heat that can change fruit character on the vine in a single sweltering day, the issues caused by rain can be fixed with manpower. Canopy management aids airflow to keep the fruit dry during the growing season, and better fruit sorting helps with fruit quality during harvest.

Such practices, of course, can also mean less fruit on the vine and less wine in the barrel. But then scarcity almost defines Screaming Eagle. Its yearly volume ranges between 550 and 850 cases each for two wines – its flagship Cabernet Sauvignon and the newer, Merlot-based blend The Flight. Screaming Eagle began making the latter in 2006, just after Kroeke’s purchase of the winery from founder Jean Phillips. Originally known as Second Flight as a nod to the winery’s bird iconography and Phillips’s tenure having been a first flight, in 2015 this was changed to simply The Flight, so as to imply a sister wine rather than a second-tier production.

Making history

Jean Phillips had little inkling her winery would gain such a reputation when she founded Screaming Eagle. Leaving behind a successful career in Napa Valley real estate, and without any winemaking experience, she purchased the then unknown site in 1986. The vineyard was already planted and had been since at least the 1940s, but its rows were a mishmash of varieties. Phillips quickly replanted it to 50 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot, and she got to understand its nuances by making home wine for a few years. Then, in 1992, in collaboration with renowned Napa winemaker Heidi Peterson Barrett and neighbouring winery owner Gustav Dalla Valle (who were also making Dalla Valle wine together), Phillips selected her favourite vineyard blocks, made her first commercial wine and sold the remaining fruit to other Napa wineries.

On its release three years later, wine critic Robert Parker gave Screaming Eagle, with its mere 200 cases, a headline-making 99 points. Almost overnight, the wine gained cult status. As the subsequent vintages garnered similar favour, the wine came to be regarded by critics and collectors alike as a Napa first growth.

By 2006, demand far outweighed supply. There was a waiting list to get on the waiting list. But some blocks had developed leafroll virus, demanding extensive replanting across the vineyard, and Phillips’s little stone winery was too small to make more than a few barrels of wine. She decided to sell. Kroenke invested in majority ownership, initially in partnership with then-sports agent Charles Banks. And with new owners, Screaming Eagle also got a new winemaking team. Hotshot winemaker Andy Erickson, then still in his 30s but already known for his work with Napa Cabernet, was appointed winemaker, alongside French oenologist Michel Rolland as consultant. Napa’s most famous viticulturist, David Abreu, was tapped to manage vineyards.

The team began replanting blocks affected by leafroll virus. They also built a new winery. But the partnership between Banks and Kroenke lasted just three years, and in 2009 Kroenke claimed sole ownership – perhaps just as well: Banks’s reputation has since plummeted after a conviction for wire fraud. Erickson hired Gislason as assistant in 2010 then departed after the season, leaving Gislason in the lead.

Symbiotic relationships

Today, the direction of both viticulture and vinification comes from Gislason, working closely with his own vineyard team to develop integrated farming techniques. (Abreu remains on retainer for emergencies, such as swift harvests in hot weather; Rolland comes on board two or three times a year for the blending.) In his gentle, understated manner, Gislason takes me to a particularly rocky section of the vineyard. ‘The site is in a convergence zone geologically,’ he says. ‘It sits on a fault line, so there is a lot of intermingling of soils.’

Volcanic stones eroded from the neighbouring Vaca Range converge with uplifted igneous rocks and are interspersed with alluvial gravels laid down by a creek coming out of the mountains. Thanks to the influence of the Napa River, there are also sections of clay. It all makes for a complex patchwork of soils. When I visit again a few weeks later, though, the scene is markedly different. Everywhere there is clover mixed through with vetch and small flowering plants pre-bloom. When I stop by in April, it is more different still, the ground erupting in colour, the vineyard covered in the clover’s crimson flowers and various pink and orange blossoms. Those winter rains have done their work.

Sheep walk the vine rows. Their snacking reduces excess vegetation, while their feet help break up compacted dirt

During the growing season, the cover crop will be left in most of the vineyard, rather than tilled into the earth. As well as helping to increase nutrients in the soils, it also keeps the ground cooler, encouraging slower ripening and retaining freshness in the wine. ‘In making farming decisions,’ says Gislason, ‘we are trying to look at not just the vines but also their holistic surroundings.’ Maintaining cover crops is just one example. Early in the season and again towards its end, after harvest, sheep walk the vine rows. Their snacking reduces excess vegetation, while their feet help break up compacted dirt. It’s an easy way of introducing more oxygen to the soil and increasing soil health. But sheep also enjoy the fresh green tips of growing vines. So, before the vine forms new buds, they are moved off the vineyard, and 90 chickens are put in their place. The birds remain there for the rest of the season, living within a movable pen engineered to fit between the vine rows and be rolled along as the chickens clear each section of vineyard. Inside, the birds are protected from predators and feed on problematic bugs found along the vine trunks and between the rows. They naturally mow the cover crops and return nutrients to the soils through their droppings. ‘The animals give us a way to think about how to do less but to accomplish more, by doing it at the right time in the right way,’ says Gislason. ‘The goal is to do simple things in a thoughtful manner – to do less but better.’

This is a strikingly naturalistic approach in a region often more associated with blockbuster wines and gilded wineries. But then, everything at Screaming Eagle is more nuanced than its reputation suggests. The vineyard is divided into 50 distinct blocks. More than half is planted to Cabernet Sauvignon; the remainder is an even split between Cab Franc and Merlot. Each of the blocks is farmed according to the specific characteristics and needs of that section – and that complexity of soils yields a distinctive signature. At harvest, the individual blocks are picked and vinified separately. The method of vinification also varies, with the cellar housing tanks of stainless steel, oak and concrete, and the different vessels serving the unique characteristics of a particular block. ‘Concrete can be useful in more floral wines,’ Gislason says. ‘There is something about the interaction of the vessel with the fruit that brings out those characteristics. Oak seems to do well to help manage and round out the fruit tannin in some Cabernet. Stainless steel works well with many things; it’s very versatile.’ After fermentation, the wines are moved to barrel for ageing, with vineyard blocks remaining separate until blending. ‘It’s all about recognizing symbiotic relationships in a blend. How different blocks interact can be magic.’

Today, it is still primarily the same blocks favoured by Phillips that form the heart of the wines. While the team makes wine from the younger vine blocks every year, so far none has made it into the final blend for either wine. Ultimately, only a quarter to a third of the vineyard makes it into the bottle. The remainder, as they put it, disappears. (The winery won’t say exactly what happens to it.)

Measuring value

The ultimate goal of such rigour? ‘We want elegant space inside the wine,’ says Gislason. It’s a notion that runs counter to most people’s view of cult wines, where heft and density are de rigueur. Many assume Screaming Eagle is also a wine of such size. But outside the winery, few have actually tasted it. Most of the wines go to collectors, many of whom are more likely to sell their allocation than drink it.

When I taste them, it is their elegance that strikes me. They are ageworthy wines, more classic Bordeaux than modern Napa, yet still with the perfumed nose and mineral line that speaks of Oakville. The Merlot has surprising and pleasing structure and poise. The Cabernet is impressively layered, fine-boned and full of presence. Like any fine wine, some vintages need more time in bottle than others.

Upon release, a single bottle of the Cabernet sells for $1,050, available only to the winery’s private mailing list in three-bottle packs. Similarly allocated, The Flight sells for $550 a bottle. (The winery also makes about 50 cases of a Sauvignon Blanc that, when I taste, I find full of vibrancy and flavour. It’s not for sale, though. The winery released 600 bottles in 2012; six of them found their way on to the secondary market and sold for $13,000.)

Bottles of Screaming Eagle on the secondary market sell quickly at more than twice their release price. With age they go for even more. In 2000, a six-litre bottle of the 1992 inaugural vintage sold at auction for $500,000. It’s a number that makes asking if the wine is worth the price seem absurd. Like fine art, at a certain point the cost of fine wine surpasses normal human standards of measure. It isn’t only about the wine itself anymore; it’s about what the wine represents and how much it is worth to those who want it badly enough. And there are many out there who want it very badly indeed.