They say you always remember your first taste of Krug, but my initial encounter with that legendary Champagne didn’t involve drinking it. I have admired the American journalist AJ Liebling since I first read him, and I still know nobody who writes as well on food and wine, particularly in mid-century France – those heady decades when the exchange rate allowed an underfunded American to live like a prince, in a country where bistro fare (la cuisine bourgeoise) and fine dining (la cuisine classique) coexisted happily and seemingly effortlessly, ably supported by diners who, in decades of daily multi-course, multi-bottle meals never consumed an E-number nor a burger bun.

Liebling was an unembarrassed gourmand, whose chief regret was the medical establishment’s post-war focus on health rather than sickness; fretting over a balanced diet was, to his mind, the cause of more illness than any number of seven-course dinners.

Liebling writes of dining with his old friend and fellow feeder Yves Mirande, who at this point is 80; he is disconcerted to hear that his friend’s doctor has recently advised against Burgundy. My own suspicion, coloured by my status as a sometime Burgundian, is that that doctor was a native of the Other Place: Bordeaux. In any case, their meal was not invalid fare.

‘After the trout, Mirande and I had two meat courses, since we could not decide in advance which we preferred. We had a magnificent daube provençale, because we were faithful to la cuisine bourgeoise, and then pintadous – young guinea hens, simply and tenderly roasted – with the first asparagus of the year, to show our fidelity to la cuisine classique. We had clarets with both courses – a Pétrus with the daube, a Cheval Blanc with the guineas.’ And then, as a chaser, they drank three bottles of Krug: ‘One to our loves, one to our countries, and one for symmetry, the last being on the house.’

It’s not that I want to go halves on three bottles of anything – particularly not after two of the world’s greatest clarets. Still, from a safe distance, I found this insouciant gourmandise marvellous, in much the same way as I have fantasies of living in the 19th century that entirely ignore such inconveniences as sexism and inadequate plumbing. And when, eventually, I was able to try Krug Grande Cuvée, it lived up to the billing. It remains one of my favourite Champagnes: the most recent, 169th edition, based on the 2013 vintage, is lightly toasted, bone-dry yet honeyed, with a lingering, appetising bitterness on the finish.

Krug Grande Cuvée, blended each year from a choice of 400 reserve and young wines that range back more than a decade, both is and is not a vintage wine, and its expression of terroir is complicated, unless you consider that terroir to be the idea of Krug (which, of course, incorporates Grand Cru vineyards). Every Champenois brain cell has historically focused on creating a wine as good in a terrible year as in a great one in what was, for generations, the chilly northernmost edge of the winemaking world.

Blending plots and years enabled this triumph over nature – which may be why a gourmand convinced himself it would offer victory over mortality. Liebling’s essay ends mournfully, but it isn’t Champagne that does for his octogenarian friend, but the lack of it – too much attention to that Bordelais doctor’s advice on abstinence destroys his constitution.

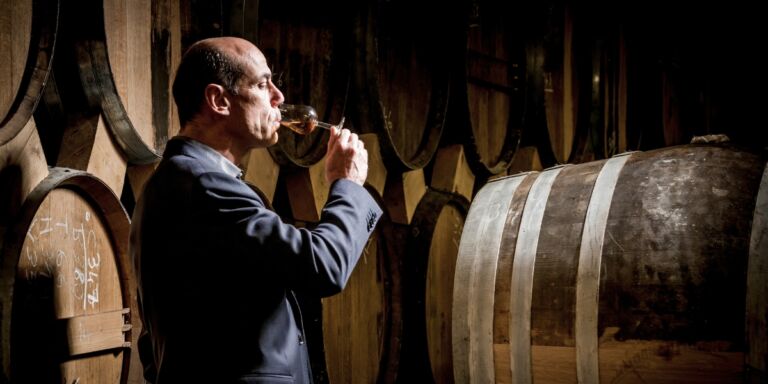

I visited Krug last week, which after a year without wineries was in itself worthy of popping a cork. The weather was atrocious: English vineyards may have extended that northernmost boundary, but Champagne houses still operate at the outer reaches of vinous viability. ‘A year doesn’t tell us what to do, it offers an outstanding spectrum from which to create the Grande Cuvée,’ says Olivier Krug, who knows exactly when he tried his first drop of Krug but doesn’t precisely remember it, since he was a baby being baptised at the time.

In a room backed by multicoloured glowing bottles – an evocation of that spectrum – I tasted the 162nd Grande Cuvée, based on 2006, and the 2006 vintage Champagne. Both were superb but the Grande Cuvée had more complexity, more depth. Champagne may currently be trying to assert itself as ‘not only bubbles and blends’, in the words of Nicoletta de Nicolo at Philipponnat, another great House, but bubbles and blends still have a lot to recommend them.

You don’t compare Beethoven and Mozart, as Olivier’s uncle Rémi Krug once responded to a question about another Champagne house’s wines, and I will not be comparing Philipponnat, which I visited next day, with Krug, except to point out that both make superlative blends and also reserve certain parcels to bottle alone. Philipponnat have been doing this with parts of Clos des Goisses, a steep, 5.5 hectare plot in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, since its purchase in 1935 (‘people thought they were crazy!’ says Nicoletta), but Krug only acquired Clos du Mesnil, its tiny Chardonnay vineyard in the village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, in 1971, so Liebling and Mirande will have toasted with the Grande Cuvée.

Philipponnat goes narrower yet, bottling a tiny segment of Clos des Goisses Pinot Noir as Les Cintres. I tried the 2010 and it was glorious: seashells and spice, delicate yet enduring, a little like the human physique. Nonetheless, for toasting, I would always choose a blend. We are not so pure, we humans: we relish life in all its exquisite flavours yet hanker after immortality; we know that comparisons are pointless, and yet we make them anyway. I will raise my glass not to beloved nor homeland but to common sense, which like the first two exists mostly as a figment of my imagination, and requires frequent administering of Champagne to continue existing at all.