I spent the 50th anniversary of Charles de Gaulle’s death in quarantine in Montreal. This wasn’t planned, I hasten to add. In fact my current location is the only reason I know about the anniversary at all: it’s amazing what you find time to read when you’ve just reached a city and aren’t allowed out to enjoy it.

In 1967, the centenary of Canada’s confederation, de Gaulle, then President of France, visited Montreal’s World’s Fair and cried ‘Vive le Québec libre!’ to the delight of the crowd, many of whom also felt Quebec should be an independent nation. Like de Gaulle, I’m a blow-in – my husband is Canadian, and we’re here to see his parents – but, I hope, a slightly less disruptive one.

Stuck inside, with just dinner to look forward to (and boy, do I look forward to dinner these days…) I’ve started thinking about freedom, and what we ask of it. Never mind grandiose questions of identity: right now, I’d like the freedom to give my mother-in-law a hug. (She loves hugs so much she was once fired – from a volunteer position, but still – for insisting on hugging a café’s clientele.) I want to order a small plate or 20, and too many glasses of great wine, at Le Vin Papillon, probably my favourite Montreal bar, or cook for the many friends here who we aren’t permitted to see. There’s stirring the pot, which De Gaulle was so good at, and then there’s delivering up its contents onto someone’s plate. Provocation is provocation, but homecooked food is love.

Helpfully, on that score, Lesley Chesterman, until recently the Montreal Gazette restaurant critic, has sent me her new cookbook, Chez Lesley, and its pages transport me into the living city. Not via so-called Quebec specialties: there’s no tourtière meat pie, sticky-sweet pudding chômeur (literally, Unemployed Man’s Pudding), or heaven forbid, poutine, that ghastly amalgamation of chips, gravy and curd cheese. No, instead, all the strands of this vibrant immigrant culture are here. Many dishes have French or Italian roots; there are curries, scones and Lesley’s Ukrainian grandma’s Chicken Kiev. Lesley is perfectly bilingual, and the occasional English word amid the French hints at the complexities of Quebec’s language wars (this is Canada’s only officially French-speaking province). But there’s no snippiness, just an unabashed gourmandise as joyous as an over-order at Vin Papillon.

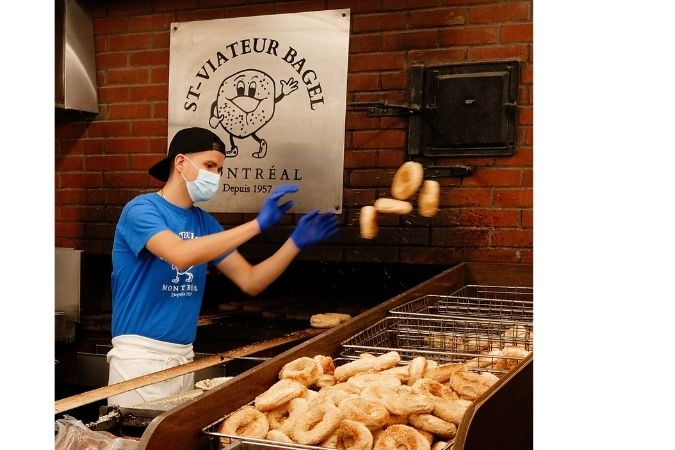

Like thousands of outsiders before me, I feel at home chez moi in Montreal, but at this point, I’d also appreciate a little liberté. I’ve been here ten days and haven’t yet bought a bagel. Forget sovereignty – I want hot, sesame-sprinkled dough, the gift of the city’s original Jewish immigrants. Today, the ovens blaze continually and Montrealers have the freedom to source fresh bagels at any time, day or night. Unless they’re in quarantine, of course.

In winter, the ice in the parks is smoothed into free rinks, and tiny children zoom past you at warp speed beneath leafless trees glittering with frost. This is my only Montreal memory that doesn’t involve food or drink. I miss shopping for the world’s sweetest corn at Jean Talon market during the few autumn weeks the corn season lasts; or eating exquisite roundels of tender octopus with Frantz Chagnoleau’s Clos Saint-Pancras Mâcon-Villages at L’Express, the French restaurant France wishes it had. You can’t discuss freedom in Quebec without mentioning the very peculiar alcohol laws (I’ll come to that), but how I miss the wine bars. Last year, I drank Sota Els Angels, a white made from the red Carignan grape, in the bohemian Bar Suzanne, where ferns spill like streamers from overhead beams; DB Schmitt’s orange Müller-Thurgau, as funky as the décor, at VinVinVin; and Domaine Tempier’s glorious red at Provisions Bar à Vin, with its butcher’s counter.

At least I’m still well supplied with wine which, here, must be bought from the government, via the SAQ (Société des Alcools du Québec) monopoly. I’m ambivalent about the SAQ. Montreal’s independent importers can only sell to restaurants, so while obscure small producers appear on wine lists, they aren’t championed elsewhere. The SAQ outlets do get small allocations of cult wines, but you need to be faster than a seven-year-old on skates to grab them.

And yet. The SAQ and its Ontario equivalent are the world’s biggest wine buyers, and that offers freedom of another kind: the range is broad, the prices keen. I remember an impulse pick, of a GD Vajra Barbera d’Alba, from a discount bin, that was so delicious I went straight back to clean out the remaining stock. Of course, I had to show up before the draconian, government-mandated closing time: 6pm (or, woohoo, 7pm on Thursdays and Fridays).

There are other constraints. At present, I’m limited to the SAQ’s online store, and without the freedom to touch or discuss an intriguing bottle, I simply return to wines I know. In captivity, I’m a less adventurous drinker. Not all closed doors are external.

Quebec is still part of Canada, to many Francophones’ irritation, and still insists on French, to the outrage of some Anglophones. It won’t sell me wine in quite the way I’d like, and right now, it won’t sell me dinner at all. But there are many kinds of freedom, and this city has tolerance, generosity, creativity and appetite, to say nothing of bagels and bottles and people I love. Vive Montréal libre! And now, please, a little liberté for me, too.