Barbados is seductive. You wake up to sunshine and the sound of racehorses being exercised in the sea. It’s 26°C. By lunchtime it’s around 30°C, so it’s time for a cold beer or Corn ’n’ Oil (the island’s signature cocktail of rum, falernum and lime juice), then a snooze. By dinnertime, the temperature has dipped to 28°C, and it’s time to head to a restaurant. You go to sleep knowing that the same thing will happen tomorrow. A Caribbean idyll.

But this is also a working island, a place of cane fields, small farms, and fishing. There is always a sense of this dichotomy between image and reality. The hotels may be full, but the profits are shipped offshore. Every so often, tech industries or pharma descend, then they leave for the next cheap site – taking the skilled workforce with them. The questions facing Barbados are both economic and existential. How can it grow, and what is its identity? The answer to both can be found in its rums.

Richard Seale of Foursquare is conceivably the world’s bestknown rum distiller. He is certainly the most awarded. He is forthright in his opinions and can converse at length about the minutiae of rum production, but he is also a true historian. Any conversation will flit between these two poles. He has perspective. Perhaps that comes with being from a family that has been on the island since the 17th century.

In the mid-1600s, Barbados was the first of the Caribbean islands to plant sugar cane and the first to make rum. ‘We started making rum at exactly the right time,’ Seale explains. ‘This was the point when people started to drink distilled spirits as a social drink.’ The island’s transformation to sugar colony was rapid, and even after other islands (Jamaica, St-Domingue [Haiti/Dominican Republic] and Cuba) outstripped it in volume, sugar and rum remained Barbados’s sole industries. Cane defined the place.

Seale shows me a 1686 map of the island, filled with a mass of sugar estates, the majority of which would have had a still. Among them is Foursquare. It’s there, slightly larger, on another map from the mid-19th century, but most of the old estates have gone, absorbed into larger plantations. ‘By then,’ he explains, ‘there were estates that only made sugar and molasses, and others that made rum.’ By 1825, Foursquare was one of the former. ‘At the peak of the sugar industry, in the 1950s/60s, Barbados had 16 sugar factories. All have gone. [A central one was built in the 1980s.] Foursquare closed in 1988. We bought it in 1994 and refurbished it for making rum.’

With no archive of rum-making at Foursquare and no marques taken up by other producers, Seale had carte blanche. He could, in theory, do whatever he fancied, but he had a clear vision. ‘From the outset, we were determined to make a Barbados style – a single-distillery blend of column and pot/retort.’ He smiles: ‘The amusing thing is that we were mocked. Bacardi was king at the time, and we were told, “No one’s drinking that old style anymore.” Ironically, now it’s the style that everyone wants – so much so that we’ve had to buy another pot to keep up.’

Rum, like any spirit, moves with the times, shifting from rich to light and back again. ‘People have this assumption that rum must have been better in the 50s and 60s, when actually it was lighter,’ he says, shaking his head. ‘We went through a period from the 1950s to the 70s when rum had to be super-light to be mixed with Coca-Cola, but we were determined to be a modern Barbados style that upheld the older ways. By modern, I mean the style that became the norm at the start of the 20th century, when columns came in – the column/pot blend. That is who we are.’ In many ways, this sums up the Richard Seale approach: historically accurate, creative, stubborn.

From the outset, we were determined to make a Barbados style but we were mocked. Now it’s the style that everyone wants

Seale’s column is a modified Coffey-style, but run under vacuum; this lowers the boiling point of alcohol, making it more energy efficient and also, its proponents argue, more efficient in separating aromatic compounds. One of the two pot/retorts is also operated under vacuum, the first in the world to be so. It’s 19th-century technology brought up to date but totally aligned with how Barbados rum has evolved – and it starts with the pot/retorts, which were adopted across the Caribbean. Why did they become the go-to here, though, and not in Scotland, say?

‘Rum was always linked to the sugar industry, which had engineers seeking innovations for efficiency,’ says Seale. ‘They were asking why they were double distilling when they could have a device that would give that result in one pass. One branch of that ended up with the column; another ended up with the double retort.’

Different stills give different flavours, but Seale is also varying ferment conditions to help expand the spectrum. ‘We want to create different marques, which is also something that’s different in the anglophone Caribbean and also the result of consolidation.’ He goes on: ‘Originally, each estate would have had its own marque. And even though the original estate might have disappeared, there was still demand for its marque, so distilleries across the region would make more than one. That’s what we’re replicating.’

Unusually, the column and pot new-makes are blended together prior to ageing. By varying the ratios, Seale effectively creates even more marques. Although a wide range of casks is used, two types – ex-bourbon and Madeira – form the base. As ever with Seale, there’s a historical precedent. ‘When Barbados was turned into a sugar colony it was deforested, resulting in trade being established with North America – oak staves in exchange for molasses and sugar.’ He grins. ‘Barbados was using American white oak 200 years before bourbon. You should call bourbon casks ex-rum. Then, similar to Scotch, we’d refill fortified-wine casks – and from the 17th to 19th centuries that was predominantly Madeira, with some Sherry.’

After ageing in either ex-bourbon or Madeira, Seale will transfer the rum to another type of cask for a period of secondary maturation. ‘Not finishing,’ he’s quick to point out. For Seale, finishing is a short-term fix often used to cover faults. What he is doing at Foursquare is more akin to Cognac-esque élevage.

In my early days, I was always told that rum couldn’t last longer than 10 or 12 years in the Caribbean’s heat, but Foursquare is releasing 18-year-old rums. There’s a shake of the head and a wry smile. ‘I don’t think there are many things that have given me more pleasure than throwing that myth away,’ says Seale. ‘Age is the single most powerful tool I have to improve the spirit. If you ruin it, it is because you didn’t know how to use that tool. If your rum comes out woody, it was in the wrong cask.’

This is just one of the various myths and preconceptions that continue to dog rum. Is there still an element of frustration that rum’s heritage is either ignored or dismissed? There’s no smile from Seale this time. ‘This narrative is shaped by the past 20 or 30 years – the dark days of rum and Coke.’

The idea of rum only recently starting to premiumise also gets short shrift. ‘That’s nonsense,’ says Seale. ‘We’ve been ageing rum for centuries. Premiumisation is not something new to us. This idea that rum is this cheap spirit that’s learning how to be premium is frustrating.’

He is on a roll now, turning to the idea that rum can only be either molasses- or cane juice-based. ‘People think rum is either one or the other, which isn’t historically correct,’ he says. ‘In the past, there was no such thing – both went in. More juice at the start of the year, more molasses at the end. I want to re-blur that line.’ To do this, Foursquare has been fermenting and distilling cane juice since 2016. ‘People said that it wasn’t the Barbados style, which is compete bunkum. Juice was always important in rum; it’s a big part of our heritage. We’ll blend the juice rum in with the molasses.’

This idea that rum is this cheap spirit that’s learning how to be premium is frustrating

There is a further factor: Barbados is an expensive place to make sugar, and the future of its sole mill – which produces some of the molasses used by its distilleries – is under threat. It provokes another existential question: can a Barbados rum be made without local ingredients? Foursquare, Mount Gay and St Nicholas Abbey have all responded to this by starting to produce their own estate-grown rums (or distillate, in Foursquare’s case). ‘It restores a tangible link with the estate and place and gives us one more reason why this rum can only be made in this location,’ says Seale.

The issue confronting rum has always been one of control, or lack of it. Like today’s hotel trade, for centuries rum was made in the Caribbean but then shipped abroad where the profits were made (and kept). What Seale, Mount Gay and St Nicholas Abbey are all doing is taking charge of their own destiny, establishing a Barbadian identity. However, that task is made extremely difficult without some form of regulatory framework. Rum made here can still be matured and doctored off the island but be said to be from Barbados. ‘It would be cheaper to buy spirit from Guatemala and ship it to Europe or the US and slap Barbados flags all over it,’ Seale argues. ‘Consumers instinctively understand Scotch or bourbon. In rum, we don’t have that, and a GI [geographical indication] is a step towards achieving that and towards allowing us to elevate Barbados. It’s not marketing but a genuine win/win for producers and consumers. I need to protect not only my brand but also my category.’

And I’d add, his island, because while Foursquare may have the scores and medals, its rums are all about a profound sense of heritage, place and identity.

Three Foursquare rums to try

Foursquare, 14-year-old Private Cask Selection

Using the classic Foursquare template of ex-bourbon and Madeira, there are baked and dried blue and black fruits on the nose here, with a hint of tropical fruits. The palate is gently sweet and silky, showing touches of oak, mace, cocoa nibs, and cooked plum. The finish both deepens into molasses and lifts with zippy citric acidity. 90 points

58%, £95, Hedonism Wines (exclusive)

Foursquare, 14-year-old Private Cask Selection

Yes, it has the same age, strength and cask make-up, but this is a different rum. It’s more molasses-led, with a fuller pot-still element. A hint of leather, liquorice, black cherry, Dundee marmalade and cassia, and then a zingy red-fruit finish. 90 points

58%, £99.95, Royal Mile Whiskies (exclusive)

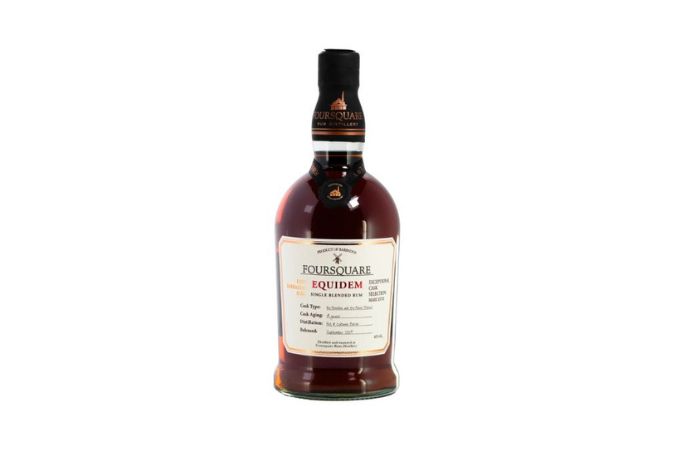

Foursquare, ECS Equidem 14-year-old

Part of the Exceptional Cask Selection range, here’s a wholly ex-bourbon matured rum blended with a five-year old that started in ex-bourbon then was transferred to Black Muscat casks for nine years. The thickest, chewiest and sweetest ECS yet, mixing mulberry, damson and heavy florals with bright tangerine, molasses and ginger. 92 points

61%, secondary market