Growing up, it was something that was offered on a Sunday. A preprandial precursor to a roast, served at room temperature, in a glass modelled on a thimble, from a bottle that was probably first opened in the Franco era. I was aware that guests usually politely declined it, as they wished they could the soggy sprouts, and, courtesy of some underage raiding of the drinks cupboard, I realised why. It reeked of antique furniture, was sweet, sickly and syrupy. Teenage life is a voyage of discovery in all sorts of ways, but this was one place that I definitely wasn’t going.

Incredibly, it took another couple of decades to give sherry a second chance. I now regard these as the wilderness years: the drinker’s equivalent of being lost in the Sahara, or sent to prison. If only I could do what Bobby Ewing did in Dallas and make it unhappen with a quick shower.

Studying for a diploma at London’s WSET meant undertaking the fortified module. As a staunch sherry-eschewer – which is much easier to say when you haven’t consumed any – it was something that I approached with a sense of trepidation. Sensibly, the educational tastings began with the bone-dry stuff: fino and manzanilla. Both styles can be an acquired taste for some, but I was immediately smitten.

And I am not alone. I know dozens of fellow former wine students who confess that they also embraced sherry in the classroom. Although initially horrified to find out what I had been missing, it has given rise to a mid-life pursuit so much more rewarding than the usual madness of motorbikes, miracle hair medications or pretending you still listen to Radio 1.

Sanlucar’s position, on the Atlantic coast, imbues manzanilla with a vital, life-affirming sea breeze salinity

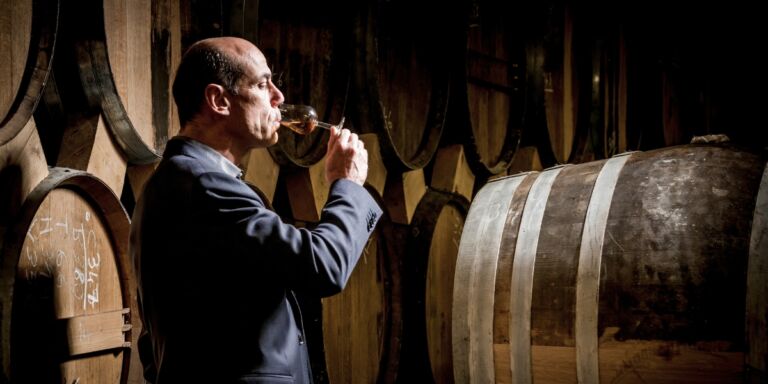

As anyone already merry for sherry will testify, there is so much to find out and, having just returned from Andalusia, I have discovered that it is the gift that keeps on giving. Bugger the Bermuda Triangle, I am much more likely to disappear without trace in the Sherry Triangle, with its vertices of Jerez de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa María and Sanlúcar de Barrameda, lost in the vast bodegas (warehouses), sampling the complex secrets of the solera, the system of barrels through which the sherry travels as it gracefully ages.

It is in Sanlúcar that manzanilla undergoes its character-defining, biological ageing process, under flor, a hirsute-looking layer of yeast that prevents oxidation. Bone dry, aromatic and fascinating, it is made the same way as Fino, from Jerez and Puerto Santa Maria, tasting similar, yet deliciously different. Sanlucar’s position, on the Atlantic coast, imbues manzanilla with a vital, life-affirming sea breeze salinity and a brininess reminiscent of a Nocellara olive, which gives it the edge over its old rival.

As delicious as they are, manzanilla and fino are merely flor-play, because there’s a sherry for everyone, from dry and crisp to super-sweet, calling at all stations in between.

I’m a huge fan of amontillado, which starts life under that protective layer of yeast then undergoes an oxidative phase, developing a wonderful, toasty nuttiness in the process. Then there’s oloroso, fortified at an earlier stage in its life, giving it a richer, more powerful, balsamic, caramelised character. And, seemingly combining the best of the amontillado and oloroso worlds, there’s the great enigma, palo cortado. Mystery surrounds its exact definition precisely because there is no definition. I am still a bit baffled, but that makes it all the more exciting.

I’m less in thrall to the sweet styles of sherry, most of them designed for the British tooth, or perhaps its dental profession, because they tend to make me think of what I hated in my youth. But I have to admit that cream sherry is better than I remember it and I do love a late-night snifter of luscious PX, or Pedro Ximénez, with its sun-dried raisiny richness.

Thanks to its astonishing diversity, sherry offers the most incredible food-pairing opportunities

For those who, like me back then, need a little more convincing, it’s also worth knowing that, thanks to its astonishing diversity, sherry offers the most incredible food-pairing opportunities. It’s easy to match an entire meal, with a style for each course, as was neatly demonstrated at the most recent edition of the Copa Jerez, an international fine-dining, sherry-pairing competition now in its ninth edition.

It also offers incredible value for money. Where else will you find a fortified wine that has undergone eight years of artisanal ageing for the price of a couple of Costa coffees? It’s crazy, but it makes it all the more compelling.

What David has been drinking…

- Krug Grande Cuvée 164eme Edition, Champagne, France, NV (£320, The Finest Bubble) A stunning assemblage of 127 wines from 11 different years, the youngest from 2008, the oldest dating back to 1990, this is a proper showstopper, with its rich, luxurious, yet perfectly balanced, citrus and hazelnut shortbread complexity.

- Lenz Riesling, Emrich Schönleber, Nahe, Germany, 2015 (£12.17, Justerini and Brooks) A thrilling ride, with rich orchard fruit, balanced by vibrant citrus acidity, textured and complex, yet nimble and fresh. Divine.

- Yangarra Old Vine Grenache, McLaren Vale, Australia, 2018 (£25.50, The Good Wine Shop) Autumn in a glass. From organic pioneer Peter Fraser, a delicious, fresh, crunchy, herb-driven wine that underlines just how exciting Aussie Grenache can be.