Many of us see Alsace as a wine region gilded in history and tradition. My thumb has often smoothed over an ornate Alsace wine label, enchanted by the medieval motifs – crests, coats of arms, crossed swords, fleurs-de-lis, winged cherubs – and the names of domains inked in faded Gothic script. I’m transported to the achingly pretty villages of the Alsace Wine Route, the oldest wine trail in France; to the cobblestone streets and half-timbered houses that shimmer in the reflection of the Colmar canal.

To visitors, the villages along the Wine Route might appear unchanged for centuries, but Alsace is not basking in the glow of the past. In fact, it’s flexing and changing, moving forward at a pace far greater than many other winemaking regions in the world.

From forward-thinking practices in vineyards and wineries to an embrace of zeitgesity winemaking techniques, these are the measures helping to pave the way for a bright future. Here are five ways the Alsace wine region is challenging the traditional.

Biodynamic dynamos

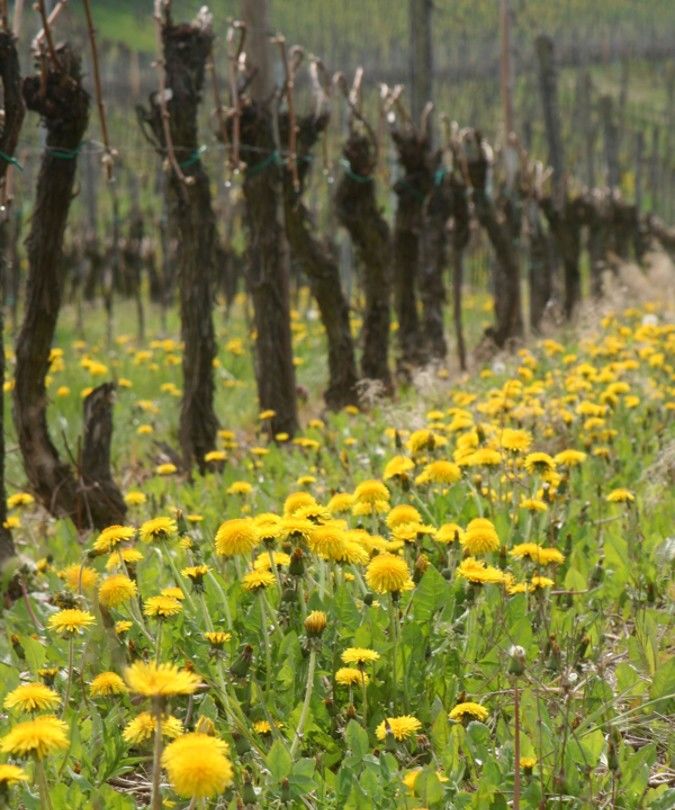

Alsace is known for its early adoption of biodynamic wine practices, influenced by its proximity to the birthplace of this farming methodology in the Upper Rhine. Today, an impressive 109 estates are certified biodynamic (as recorded in 2021).

Of course, the climate is on Alsace’s side. ‘It’s easier here than other regions to go biodynamic because it’s drier,’ says Eddy Faller, whose mother, Catherine Faller of Domaine Weinbach, started biodynamic farming methods in the vineyard in 1998. Alsace is the second driest region in France (Roussillon takes the top spot), with the Vosges Mountains shielding the area from rain and humidity. A low risk of fungal disease in the vineyard means conditions are ideal for biodynamic viticulture.

‘Ninety-five per cent of what you will have in the glass is done outside,’ says Sophie Barmès of Domaine Barmès-Buecher, where all 17 hectares are biodynamic. ‘In the cellar, we follow the wine, but the job is done.’

Unlike many other world winemaking regions, it’s not the new generation who have introduced the biodynamic trend to the family estate. Alsace has more than 20 years of experience in biodynamics. ‘All the big estates were doing biodynamics first,’ says Celine Meyer of Domaine Josmeyer, which has been biodynamic since 2000. ‘We followed their lead.’ These estates can now truly assess the effects biodynamic practices have had on their wine. ‘They taste better,’ says Meyer. ‘The grapes are more lively, the yields are lower and the wines are more concentrated.’

Drier and drier

‘Our philosophy is to make elegant, fresh, gastronomic styles of wine with less residual sugar,’ says Georges Lorentz, winemaker at Gustave Lorentz. Once a region famed for sweet and off-dry wines, this new philosophy has spread throughout Alsace.

‘The wines are getting drier and drier,’ says Barmès. Barmès-Buecher has been making Pinot Gris in the dry style since 2018. ‘But what’s hard to achieve with dry wines is complexity and depth. The time of picking is key.’ Céline Meyer at Josmeyer, where dry wines have been part of the house style for some time, agrees: ‘The aim is not to avoid the tenderness, but to preserve the freshness’.

With the preference for dry wines increasing around the world, Alsace’s famous sweet wines have been declining in popularity, though it’s not only market trends that have determined the shift. Several producers cite climate change as the reason. ‘Noble botrytis is in decline because of the climate – the window between the day and night temperature has narrowed,’ says Barmès.

Plus, while the vendange tardive wines of the region are still revered by winemakers and wine lovers alike, they are becoming more difficult to make because of the unpredictable weather. Olivier Humbrecht of Domaine Zind-Humbrecht even suggests real vendange tardive is ‘extinct’ – with the last traditional harvest back in 2010 – and that people should ‘enjoy it while they can’.

Putting a label on Alsace wine

Despite the allure of those traditional Alsace bottles, many winemakers are switching things up. ‘The first thing I did was change the labels,’ says Margot Ehrhart, who is taking over operations (along with her brother Florian) at family estate Domaine Saint-Rémy. The new labels are clean and modern, with four monochrome images of rocks on a white background. ‘Alsace Grand Cru’ is in sans-serif capitals, a far cry from the traditional Gothic-style script.

Domaine Josmeyer is working with local artists. On the label of Le Kottabe, the 2021 Riesling, there is a painting of Oberon over a midnight blue background. ‘Blue is the colour of the soul,’ says Meyer. ‘The colours represent different elements of the wine.’ Meanwhile, the labels for some of the new Gustave Lorentz wines are among the most contemporary. The vin nature 2021 is called ‘Wine Not?’ and its hazy vin orange 2021, though in a traditional flute bottle, displays a neon orange label with a multi-coloured scribble on it: ‘Qui l’Eût Cru?’ (which translates as ‘who would’ve believed that?’).

Estates in Alsace are also looking at more sustainable packaging choices. Cave de Ribeauvillé, the oldest cooperative in France, is now using recycled paper for its labels. ‘We are going in a new direction where we are focused on the environment,’ says export manager, Estelle Windholtz.

A connection with terroir

With every passing year, the winemakers of Alsace are learning more and more about their terroir and at many estates, the notion is front and centre – often literally, with rocks on the tasting table. ‘We are very focused on the soil,’ says Margot Ehrhart. ‘The soil is our strength.’

At Domaine Bohn, a 300-year-old family winery in Reichsfeld, terroir is the defining element in the character of each wine. The domaine has vines planted in a variety of soils, including schist, sandstone and volcanic soils with layers of ash. According to winemaker Bernard Bohn, schist makes a ‘very straight wine,’ with nice minerality and freshness. When mixed with quartz, the wine gains ‘a lightness’. Schist is the reason he would describe his 2013 vintage Crémant as ‘linear’, while the sandy soils beneath his Muenchberg plot bring a ‘playful’ character to the Riesling Grand Cru Muenchberg 2019. ‘It’s like pinpricks on the palate,’ Bohn says. ‘You can feel the sand.’

Celine Meyer from Domaine Josmeyer describes specific plots as if they possess individual personality traits. ‘“Hengst” has a large character,’ she says. ‘The wines coming from the Hengst take time to express themselves.’ In contrast, the 2018 Grand Cru Brand Riesling is ‘a very pure wine: it wants to fly, it’s like a flashlight, like a laser.’

In a similarly poetic approach, Sophie Barmès feels her family’s physical proximity to the vineyard helps them to understand and connect with the earth. ‘All of our vineyards are close so that we can go around them every day,’ she says. ‘We want to be close to our terroir.’

Showing some skin

If the pioneering approach to biodynamics is anything to go by, it isn’t a surprise Alsatian winemakers are experimenting with techniques and styles in the winery, too. Orange wine is beginning to appear in more collections, even if the home market might not be quite prepared for it. ‘The UK will take it, but it won’t sell in Alsace – it isn’t ready,’ says Meyer about the Domaine Josmeyer ‘Kamikaze’, a skin contact Pinot Gris. ‘It’s a new challenge and we want to make something different from our father.’

Domaine Bohn also has an orange wine, Volcanique 2018. A blend of Sylvaner, Riesling and Pinot Gris, it was aged for a year on the skins in old oak, which, according to Bohn, ‘makes it smoother’. It’s a bold, unapologetic burnt orange in the glass with notes of bergamot, oolong tea and roses, alongside grippy tannins. ‘The idea was to make an orange wine to drink in years to come,’ says Bohn. ‘It’s not the most easy wine we make, but it is the most complex.’

Don’t be fooled into thinking it’s only the small, bohemian estates making orange wine either. As well as the aforementioned ‘Qui l’Eût Cru?’ from Gustave Lorentz, Dopff au Moulin, one of the most historic Alsatian wine producers is making a Vin Orange from Gewürztraminer. Who would’ve believed that?