Before the word ‘factory’ gathered its modern associations – hellhole or production line, marvel of efficiency or source of nostalgia – it meant a trading post: a gathering point for a group of factors, or foreign traders. In Porto, those factors were British port shippers who, in the 1780s, built themselves a grand granite meeting-house in this breathtakingly lovely Portuguese city on the banks of the Douro river.

The British had been exporting Portuguese wine since at least the 17th century, when the light reds from Minho (the area now best known for Vinho Verde) made up some of the shortfall in French wines caused first by trade wars then – with Napoleon – by real ones. Eventually, they realised that there was more profit in the rich reds to be found further up the Douro, but this wasn’t what you’d call a straightforward exchange.

Back then, the road route was precipitous (it still is) and the un-dammed river wild and dangerous. By the time you’d negotiated those jutting granite outcrops and life-threatening rapids, the barrels of wine on your ship left half-full so they’d float if they went overboard, you needed more than a light red: you required fortification. Which is, of course, what port became famous for.

The Factory House is still an exclusive club of British-owned port shippers and has retained its 18th-century feel, from the display cases of porcelain dinner sets to the twin dining rooms which allow the post-prandial vintage port to be tasted (blind, of course) with the same configuration of guests but away from the debris of dinner.

While staying in Vila Nova de Gaia just across the river, I was invited there to lunch by the Graham family, owners of Churchill’s. There have been port-making Grahams since 1820, but when in 1970 his family sold up to Symington’s, another venerable firm, Johnny Graham, then in his 20s, decided to start afresh – a resolve somewhat similar to a deposed royal deciding to found his own dynasty. First, you need a kingdom.

There are, Graham explained to me over lunch, strict rules about how much port each shipper must hold in reserve, which is a problem if you’re just starting out. He managed to collaborate with a grower who had held on to large stocks, and Churchill’s was launched.

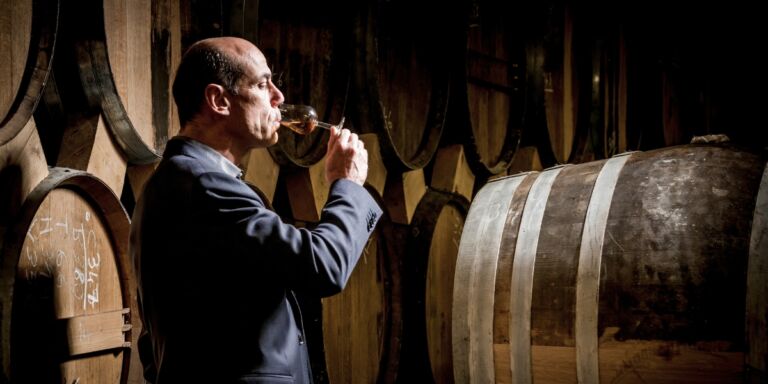

Now, his daughter Zoe and son-in-law Ben Himowitz are taking over. To see them, in the Factory House cellars, proudly displaying the 12 dozen bottles that are the initial fee for entry, is to comprehend port’s complicated relationship with time: the blend of youthful brashness and tradition, fresh-fermented wine and the judicious dose of brandy that creates a drink which mellows and improves with age. With luck, Zoe and Ben, lively newcomers to a very old business, can do the same for Churchill’s.

Johnny Graham has an old-fashioned Englishness compatible with long habitation elsewhere, profiting from the amicable understanding between two countries whose trading agreements go back to the 14th century. He arrived at the Factory House in suit and tie, wincing slightly when his son-in-law, a 30-something American, showed up in open-necked shirt (to the great relief of my husband, who doesn’t travel with a selection of ties). Ben and Zoe are the fresh infusion, and many of the more unusual Churchill initiatives are their doing.

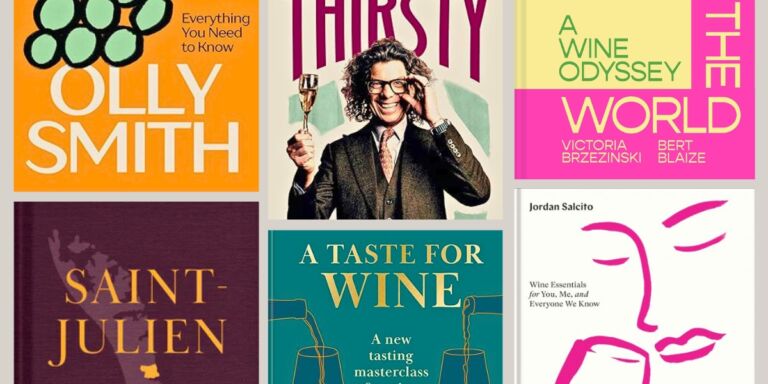

Earlier this year, I attended a Zoom session of Port Club, the family’s solution to both the pandemic and the wavering interest in strong, sweet after-dinner drinks. Sign up and three bottles arrive quarterly: an ‘anytime’ port, a ‘right time’ port and a ‘one time’, or vintage, port (‘We wanted to communicate the fun of port,’ says Himowitz, brightly). For the moment, all are from Churchill, including some exclusive blends, but they talk about bringing in other, smaller houses, and I hope they do: port’s survival can’t depend on a single producer, however dynamic.

What makes this very different club work – helping fight port’s reputation as a stuffy drink for gouty old men, a label both grossly unfair and, historically, largely true – is the quirky rapport between Johnny and Ben. The two men are so obviously different, yet so mutually respectful. Churchill’s, just 40 years old, may lack the greatest ports of the most venerable shippers, but the Grahams are chipping away the rocks and building the dams so that port can move more freely towards the future.

I am a big fan of the strong dry Douro reds made in increasing quantities by the likes of Quinta do Noval or Quinta da Pacheca. But I wouldn’t want to see them replace port, which has withstood French invasions, the phylloxera catastrophe and a journey down the river only exceeded in difficulty by the slow, laborious voyage back, boats hauled against the current by oxen that often did not survive the job.

The Factory House bears witness to the long-standing friendship between England and Portugal

After lunch, we were shown the library, with its 1947 letter from Princess Elizabeth thanking the factors for the wedding present of a pipe of port, its century-old copy of The Times, changed daily, and the immense trove of books ranging from serious tomes to a 19th-century handbook on How to be Happy Though Married.

From the full, cast-iron kitchen upstairs (upstairs, in an era before mechanical winches) to the 15,000-bottle cellar, fruit of the obligatory supply, by each member, of 12 dozen of any declared vintage, the place bears witness to both permanence and continual change, as well as to the long-standing friendship between England and Portugal and the wine that has flowed, sometimes turbulently, through it.

Afterwards, slightly dazed from lunchtime port and time travel, we walked the riverside, admiring the famous port names blaring above shippers’ lodges where the port was once required to age between its waterborne arrival and its departure abroad. Much of it still does, and several of those lodges welcome tourists, while on the slope above them rears the enormous new museum megaplex, World of Wine, both containing and overlooking the rich history that lies along this river like sediment in a bottle.