Even at 9:30am in early May, Gabriel Sanchis’ Valencian vineyard is hot. Rosemary and garrigue herbs spill into the plot. We’re most definitely in the Mediterranean.

Yet Sanchis’s La Lloma 2021, an equal blend of local grape Bonicaire and the area’s red mainstay, Monastrell, is wonderfully fresh and balanced – and only 13.5% alcohol. ‘They’re easy to drink, these wines,’ smiles Sanchis, winemaker at Can’ Leandro. ‘I’m a lover of fresher, Mediterranean wines.’

The tension between freshness and power is one of few uniting characteristics of the wines of Valencia, the Spanish province that sits to the north of Murcia and its scorching southern heat.

It is only over the past decade or so that anyone has paid Valencian wine much attention. Until the end of the last century, the vast majority ended up sold in bulk. Pablo Calatayud, pioneer at Celler del Roure, says that when he started in 2000 there was just one other producer in the region that wasn’t part of a co-op. Since then, a new generation of winemakers has started to transform Valencia’s vinous reputation.

In the north, the Alto Turia and Valentino DO sub-zones of the region are to be found in the hills rising to the northwest of the city of Valencia; some of the vineyards in Alto Turia are at altitudes above 1,000m. This is the eastern edge of the central Spanish meseta, with extremes of temperature both across the seasons and diurnally; despite the proximity of the sea, summers are very hot.

Valencia’s main white is Merseguera, often blended with Malvasia or Macabeo. It’s floral and herbacious, with similarities to some Italian and Greek varieties. ‘We’re looking for freshness,’ says Juan José Martínez Palmero, winemaker at Bodegas Terra d’Art, of his precise Flor de Ahillas Blanco 2022, which is 100 per cent Merseguera. ‘Our terroir is about minerality.’

For reds, local grape Bobal is king. But now some growers are also using cooler climate Spanish grapes. At Bodegas Terra d’Art, Martínez uses Mencia and Prieto Picudo, almost forgotten locally, in some of his reds; indeed, his fine top cuvée, Bocapiedra, is 100 per cent Prieto.

Immediately to the west, the Utiel-Requena DO is even more firmly Bobal country. It remains a challenging environment, at up to 900m in altitude with extremes of temperature and rainfall; ‘The land here is punished,’ says Paco González of Bodegas Murviedro. Moreover, Bobal is not an easy grape with which to make fine wine, as its tannins and acidity can easily lead to a rustic and even astringent final product.

But as González comments, ‘You have to work with the materials you have’, and growers like Murviedro have shown how distinguished Bobal can be. Their Sericis Cepas Viejas 2019 uses some of the area’s very old bush vines and is sweet, spicy and complex but bright and fresh too.

Meanwhile, there are fine wines now also being made here from international grapes, such as Murviedro’s CV05 Cabernet, a small-parcel cuvée bottled as DO Valencia. And while Rodolfo Valiente’s Bobals are serious, his top Vino de Pago wines are all international varietals such as his elegant, focused Pago de los Balagueses Syrah.

DO Valencia’s southernmost sub-zone, Clariano, is quite different. It is closer in terroir – and is similarly dominated by Monastrell – to the neighbouring province of Alicante: the Valencia DO’s reach is determined by provincial boundaries, not grapes. Yet Clariano is different.

‘It’s a microclimate,’ explains Gabriel Sanchis. Levant winds coming off the Mediterranean meet the continent, while limestone retains water. But the variations of temperature can still be extreme, from 38 degrees Celsius in summer down to -5 in winter. And he admits that this is a very dry year.

Down the road, that worries Rafael Cambra. We stand on high ground surveying the valley in which most of his vines are planted. The hillside opposite us looks almost devoid of vegetation. ‘By this time of year it would normally be up to here in greenery,’ he says, pointing to his knee.

Yet Cambra is adaptable. He first worked in Rioja at a point in the early 2000s when Priorat was seen as the model for boutique Spanish wines. So when he started out on his own, he used barriques.

‘But then we realised the wines don’t need new oak,’ he says. ‘You need balance to age wines, not extraction and power.’ That is evident in Cambra’s Uno 2020, made with Bobal from 65 year-old vines: sweet fruit, concentrated, almost crystalline, yet fresh.

You need balance to age wines, not extraction and power

Cambra is also one of the pioneers of forgotten local grapes, such as the lighter, late-ripening Forcallà. But the producer that has led the way on such varieties most single-mindedly is Fil.loxera, the project of husband-and-wife team Pilar Esteve and José Domenech. ‘We don’t want to make wine according to fashion,’ says Esteve. ‘If we like it, we stick with it.’

They have rescued near-extinct local grapes such as Arco, making highly distinctive, low-intervention cuvées. These are literally garage wines: made in tubs in their yard and raised in small tanks in an outbuilding and barriques stacked in their garage, surrounded by kids’ bikes and sports equipment.

The results are impressive in cuvées such as La Mujer Caballo 2020 (100 per cent Arco): sweet, expressive fruit with eight months’ time in oak beautifully integrated – and tasting nowhere close to its 15% alcohol.

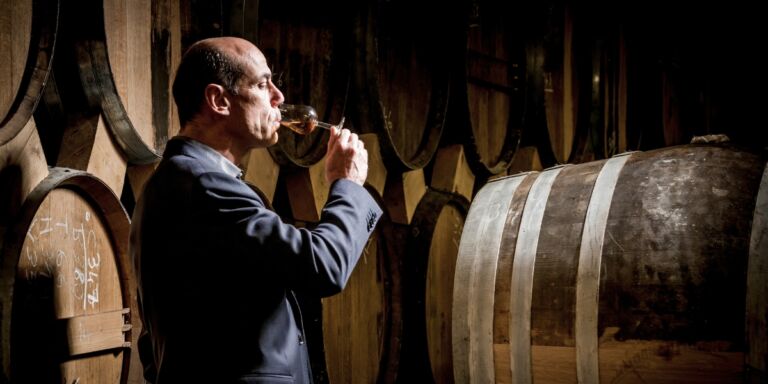

It’s a blend of the traditional and modern, underlined by Pablo Calatayud as he shows me the dozens of old tinajas (amphorae) buried up to their necks in the cool of Celler del Roure’s old cellar, hewn out of limestone long ago by a previous owner. Yet his Safra, 70 per cent from local grape Mandó, tastes fresh, savoury, individual – unmistakeably the product of a modern approach to old grapes.

‘This region is a work in progress – it’s still developing its identity,’ says Paco González. The two main DOs and Valencia’s sub-zones may well diverge further, but this is already a region that deserves to be better known beyond its sunny hills.

Valencia wine zones to watch and the bottles to try

DO Valencia – Alto Turia

High-altitude vineyards northwest of Valencia yielding aromatic Merseguera and other whites, as well as some vibrant Bobals.

Producer to watch: Bodegas Terra d’Art (see above)

Wine recommendation: Flor de Ahillas Blanco 2022 (Merseguera)

DO Valencia – Clariano

Warmer vineyards in the far south of the Valencia province, with a concentration of forward-looking producers. Reds, mostly Monastrell, plus Merseguera and other whites.

Producer to watch: Can’ Leandro (see above)

Wine recommendation: La Lloma 2021 (Bonicaire/Monastrell), £13.50, Amps Wine Merchants

DO Utiel-Requena

In the high, dry area west of Valencia. Fresh reds from old-vine Bobal with increasingly serious wines, including those from several Vino de Pago estates.

Producer to watch: Montesanco – a newer producer near Requena, growing grapes biodynamically at an altitude of 750m

Wine recommendation: Món Bobal 2019, £32, Crystal Palace Wine Club (2018 vintage)