How did a fermented agave sap drink set the foundations for Tequila? The origins of Tequila are intrinsically linked to Mexico’s Indigenous people, and it’s important to set this distilled agave spirit in the context of their lives, culture, and experiences.

The story of pulque

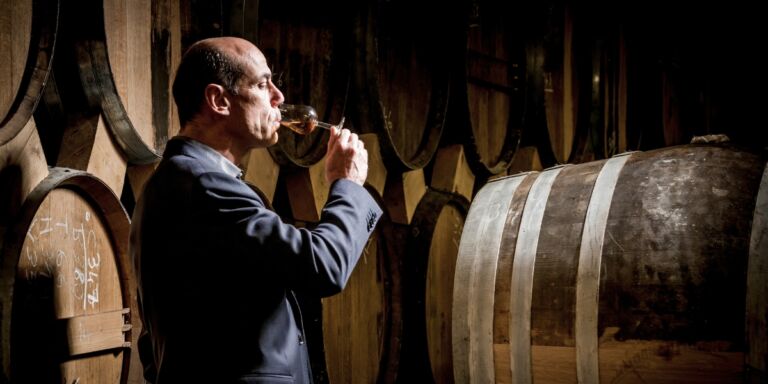

The story begins with pulque and its cultivation by the Aztecs in the Mesoamerican era, before the arrival of the Spanish. This story gives us an idea of where using agaves to make drinks may have originated before the introduction of distillation. Made from fermented agave, pulque is often misconceived as the original Tequila (or mezcal). While it is certainly a precursor of sorts, pulque is a drink entirely of its own merits. The first documentation of pulque appeared in a mural from 200CE (lead image). It is made using aguamiel (honey water or agave sap), which is tapped from pulqueros (agaves) and fermented naturally to produce a milky drink of about 4%–5% ABV. In daily Aztec life, pulque was mainly used by priests in religious rituals and in sacrificial ceremonies. Over time, it was served in pulquerías where men (women were prohibited) would debate politics and put the world to rights. In their book Agave Spirits, Gary Nabhan and David Suro Piñera write of pulque being a “prehistoric powerhouse” when it comes to the agricultural push of agaves.

Pulque is also intrinsic to the legend of Mayahuel, a goddess associated with the maguey (agave) and often spoken about or referenced in the history of agave-based drinks, including Tequila. There are many different versions of her story, perhaps most prevalent being that she fell in love with a human and bore his 400 rabbit children, which she fed with pulque from her 400 breasts. Also seen as a goddess of fertility, her story represents the importance that was placed on the sacred agave plant and its ability to clone itself and provide for its people. Depictions of Mayahuel can be found throughout history, including drawings, statues,and carvings. These include the Codex Borgia, a pre-Columbian 16th-century pictorial manuscript, and a carving in the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

The Spanish invasion

The year 1519, when the Spanish invaded Mesoamerica, marks a pivotal moment in the history of Tequila. It set in motion a change in alcohol production, eschewing traditional practices, and the advent of what we now know as Tequila.

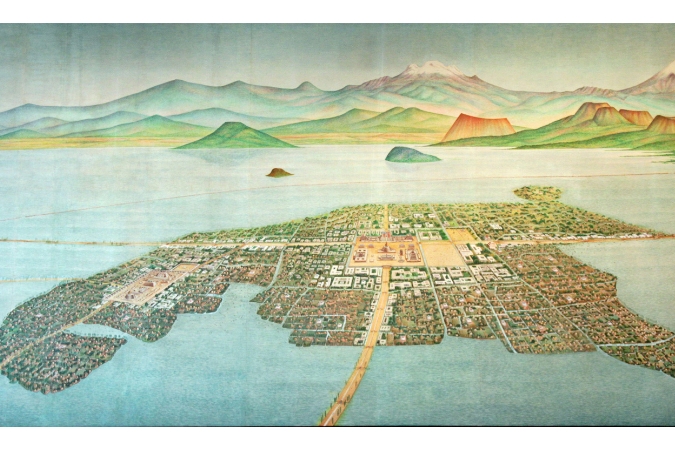

In the early 16th century, the Aztec Empire ruled over most of present-day Mexico. Led by the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and aided by political rivals of the Aztec ruler Cuauhtémoc, the conquest of the Aztec Empire began with the fall of the capital, Tenochtitlán, in 1521. The Spanish conquerors established Mexico City on its ruins. Nearly a decade later, and the conquest of the town of Tequila in Jalisco and then the securing of the city Guadalajara began the Spanish intervention on alcohol production.

Recent evidence indicates that distillation for ritual drinks existed before the Spanish arrived, perhaps as early as 600BCE, but the Spanish quickly put steps in place to accelerate the commercial production of distilled drinks.

Initially, it’s thought that the Spanish distilled agave in mud stills to quench their thirst for brandy. But the first big step was opening trade routes to colonies in Asia and America. Filipino migrants introduced stills more reminiscent of what we know today, and began distilling agaves into what was called vino de mezcal. By the early 1600s, the first distillery of scale was established in Tequila. (It’s important to remember that Indigenous people’s ways of working, culture and production form the roots of this Mexican spirit. While the Spanish may have brought with them the formalization of the category, there is increasing new evidence that distilled drinks existed in pre-Hispanic Mexico. As with many colonized countries, its people get lost in the story.)

Tidal change

By the mid-1700s, production was considerably ramped up. José María Guadalupe de Cuervo was given formal permission to start making vino de mezcal commercially by the Spanish King Carlos IV, having made the product since 1758. The Sauza family quickly followed, and were most likely joined by lesser-known, smaller, but by no means less pioneering makers. The next 70 years represented more change for Tequila. The Mexican War of Independence (1810–21) threw production into flux as exports were compromised. But with the securing of Mexico’s independence, vino de mezcal became more popular than ever and began its association with the word ‘Tequila’.