One evening in late September 2016, the church of St James the Great in Clapton, east London, was preparing for a memorial of sorts. A trestle table stood laden with great vats of Jamaican curry, and a queue for the bar ran back towards the pews as the congregation, casually attired and strikingly diverse, pottered in from the street.

The church – an imposing red-brick building in one of the city’s most revitalised boroughs – was enjoying a midweek incarnation as home to the Church of Sound, an occasional live jazz music event that had begun in the spring of that year and had already garnered a reputation as one of London’s hippest nights. That evening, they were staging a tribute to the American jazzman Bobby Hutcherson, famed vibraphone and marimba player and Blue Note alumnus, who had passed away the previous month. The crowd – now squeezed into the pews sipping cups of red wine – was a jumble of jazzheads, marimba fans and unapologetic hipsters.

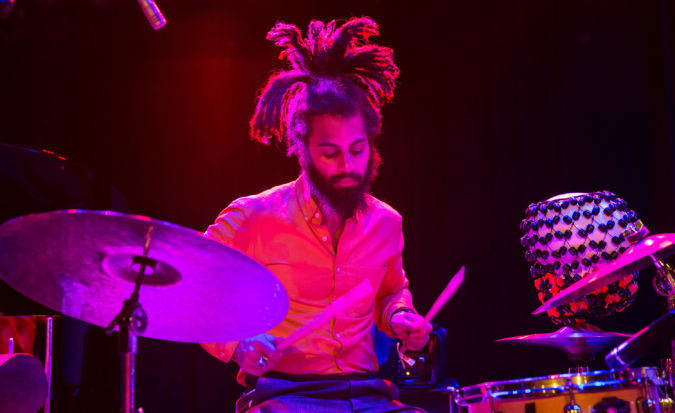

The allure was not simply the celebration of Hutcherson’s music; it was also the assortment of players assembled for the occasion, among them recent British jazz-scene luminaries such as vibraphonist Orphy Robinson and trumpeter Byron Wallen. But there were newer attractions, too: the up-and-coming saxophonist Nubya Garcia and, perhaps most of all, Moses Boyd, the extraordinary young drummer from south London whose style of playing – polyrhythmic, intense, unfettered – positions him somewhere between Max Roach and grime, New Orleans and thrash metal. As Boyd took to the stage, a ripple of anticipation spread through the room. It was a remarkable night, at once unhurried and electric and joyous. Later, it would be crowned Jazz FM’s Live Experience of the Year.

Philip Larkin once wrote of how, for him, ‘jazz was that unique private excitement that youth seemed to demand’. And indeed, it has been a matter of some disappointment that, for a while, the youth and excitement appeared to have faded from jazz, as it became the preserve of a largely white, male, middle-aged crowd – something to savour seated and reverentially near-silent.

What that evening at St James the Great epitomised was the thrill of London’s new jazz explosion, a scene that is far removed from the long-standing and more formal jazz clubs – flourishing in unexpected corners of the city, spilling out of unlikely venues and revealing a generation of young musicians who play a style of jazz that is uniquely and distinctly British.

At Total Refreshment Centre in Hackney, Steez in south London and Jazz Re:freshed in the west, artists such as Boyd and Garcia, saxophonists Shabaka Hutchings and Binker Golding, tuba player Theon Cross and a host of their contemporaries have been playing shows that have brought new verve and vibrancy to the genre. In the first half of 2018, Spotify saw the number of UK listeners under 30 streaming its Jazz UK playlist increase by 108%. Should you need any further convincing, consider that the favourites to win (and cruelly pipped to the post) at last year’s Mercury Prize were Sons of Kemet, a new jazz supergroup made up of Hutchings, Cross and drummers Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick.

It is 16 years since Justin McKenzie co-founded Jazz Re:freshed at Mau Mau Bar in Notting Hill. In those days, they relied on booking a big-name act from the US to draw an audience large enough to justify staging fledgling British jazz artists as support. Over time the night became a label, and around five years ago McKenzie began to notice a change. Rather than the traditional jazz performances, where ‘you sit down, and the presentation is really dry’, he saw performances that felt more like club nights or rock ’n’ roll shows, and he watched young artists coming up through the conservatoires who gladly called themselves jazz musicians and who brought with them audiences who were younger and, frequently, more ethnically diverse. And he saw a new generation of female musicians taking centre stage. ‘Five years ago at Jazz Re:freshed, 99% of female artists were vocalists,’ he says. ‘But the confidence now is for women to say, “I am the band leader.” It’s not tokenism – these are fantastic musicians.’ These days, with a devoted domestic and international audience, McKenzie says Jazz Re:freshed rarely books big names from abroad: ‘It doesn’t even occur to us.’

Among those who found their feet at Jazz Re:freshed is pianist Ashley Henry, who will release his full-length debut this spring. Henry was a latecomer to jazz – a BRIT School student who heard Jason Rebello’s Make It Real when he was 18 years old and from that moment felt, ‘I don’t care about anything else so long as I can play like this.’ Until that point, Henry had regarded jazz as ‘this thing that was untouchable’ – something with its own set of rules, that belonged in the city’s rarefied clubs and had little bearing on someone of his age or background. ‘So I understand it, this stigma that jazz has,’ he says. But what his part in the new jazz scene has shown him is that, ‘really, jazz is just this reflection of who you are.

It’s amazing to be involved with a crowd where we’re playing in unconventional places – it takes away that potential stigma. Jazz like this breaks down barriers. It takes it back to where it used to be. Because back in the day, jazz was cutting edge, and it was inclusive, not exclusive.’

Back in the day, jazz was cutting edge, and it was inclusive, not exclusive

There was a moment when Moses Boyd felt something had shifted. At the start of last year, he played a gig at Corsica Studios in south London. ‘It sold out quite quickly,’ he recalls. ‘We had strobe lights and smoke. And then afterwards my sister said, “Did you know there was a fight down the front?”’ He laughs. ‘And I’m not advocating fighting, but it clicked: something had changed. It’s not the safe and reserved crowd I’m used to getting.’

Boyd found jazz drumming via a school music teacher who introduced him to the work of Max Roach and Tony Williams and then watched his young student bloom. ‘Back then, there wasn’t an interest in jazz,’ Boyd says. ‘And the audiences didn’t look like me – it was a different demographic. I remember going to gigs and being the only young black person there. I went to the Chick Corea reunion show, and we were the youngest people there by a country mile.’

Over time, Boyd found his peer group. ‘There were a lot of musicians running parallel to me,’ he says. ‘United Vibrations, Henry Wu, Shabaka Hutchings, Nubya Garcia…’ But still, they felt somewhat at odds with the jazz establishment. It was, he says, ‘a pure, tumultuous and hard time. You had to struggle to get heard.’ And so, there was a joy and a liberation in playing venues such as Church of Sound, where ‘it felt more natural and more right. It was the type of space where I felt the type of music we were making should sit. I felt it fitted those environments and those people. It was what I was after.’

If there are qualities that mark out the sound of new British jazz, they are surely a collision of the sounds inherited and absorbed by many young Brits: multicultural, multigenre, electronic, acoustic – the familiar reconjured and rethought. Henry speaks of a certain ‘rawness’; McKenzie mentions how many of the new generation of musicians are seeking their roots, reaching back to the influences of their Caribbean or Indian heritage.

‘For me, it’s the rhythms,’ says Boyd. ‘A lot of the rhythms around American-based jazz can be attributed to swing rhythm, though there are a lot of other rhythms around and about that. But in the UK there are a lot of rhythms that interplay and are heavily influenced by our club culture and our sound systems. The UK has birthed a lot of great rhythms – jungle, garage, two-step, grime, ska…’ Of his own records, he would cite his Absolute Zero EP as an example of that conglomeration of rhythmic influences. ‘It was me trying to draw together the acoustic and the electronic and the jazz rhythms,’ he says. ‘Though, of course,’ he adds, ‘someone else might say something like Rye Lane Shuffle…,’ referring to the gritty, broken-beat 12-inch he released in 2016 – mixed by revered electronic artists Four Tet and Floating Points – that now fetches stunning sums on the collectors’ market.

‘But what is unique to the UK?’ he wonders, and pauses for a moment. ‘The UK is more gritty, it’s got its own melancholy,’ he says. ‘The American sound is bolder. The best way I can put it is that, in the UK, the sound is about subtle excellence.’